Table of Contents

Mandate:

Evaluate the high-level economics of an adventure park and waterpark in Panama for Isthmians Development Advisers/NSB Caribe, a local promoter.

What follows is an extended preview of a full-length report, available in our store.

Market Context

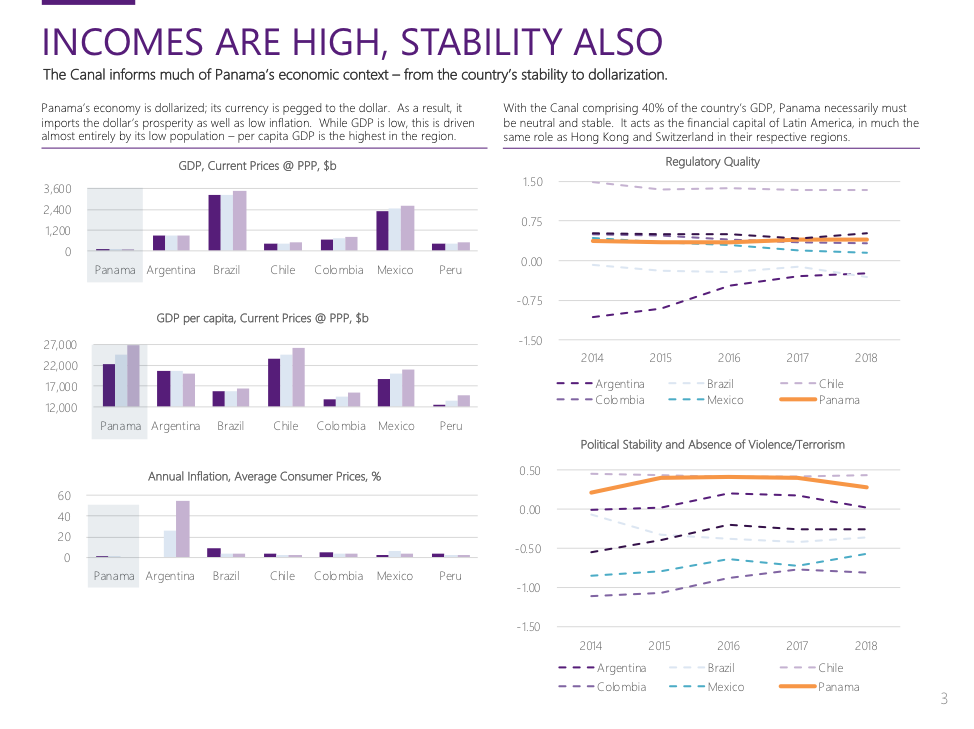

Panama is a small country in Central America, but the economy is dollarized, with the currency pegged effectively at a 1:1 rate with the USD. You might have heard of the Panama Canal, the waterway crucial to world trade.

The canal drives GDP directly and also indirectly, facilitating the development of a regulatory environment, political & monetary stability, and financial and other trade services that make Panama a favored location for investment in Latin America.

1. The result of these conditions is an economy with relatively high per capita expenditures, with over 80% of the population earning more than $20,000 USD.

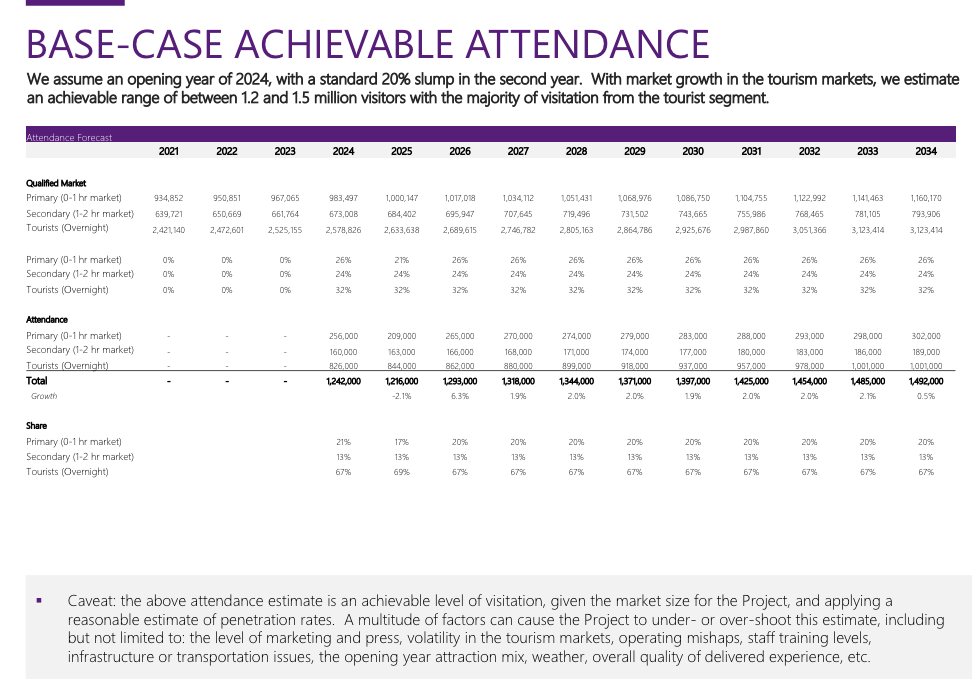

2. Despite their number, however, the resident population is not the target market. Tourists are, which have increased in number at a low (<=2%) but stable rate during the past decade and now total over 2 million annually. In total, the qualified market size is approximately 3-4 million. This places an upper bound on achievable attendance.

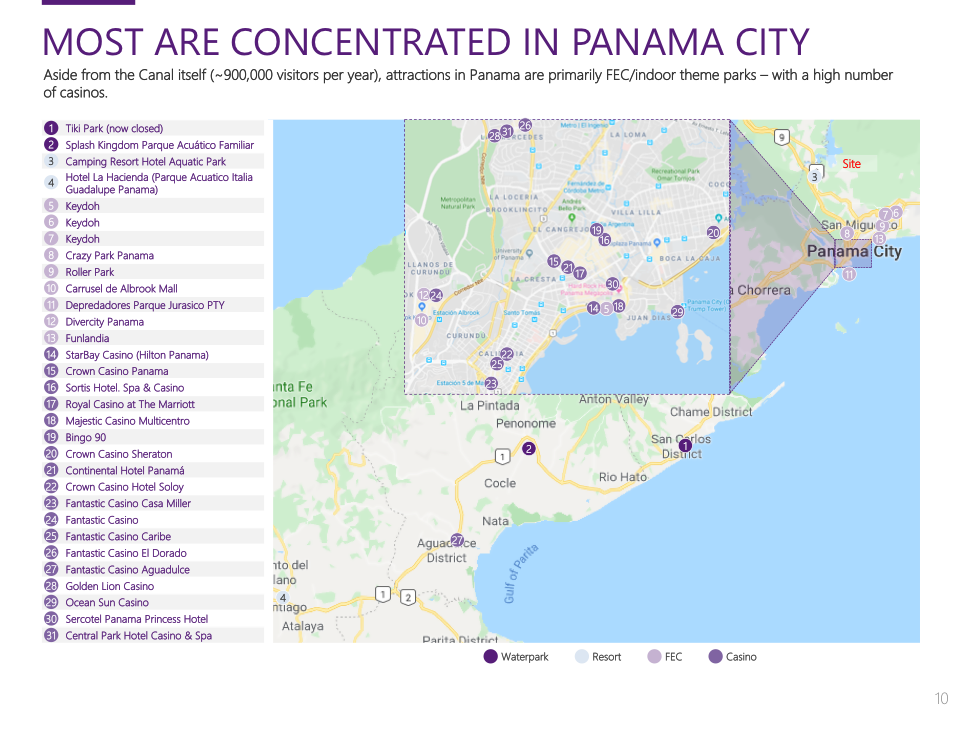

3. The main attractions in Panama are indoor attractions (FECs) and waterpark-based ones, whether in a standalone format or resort-adjacent. The Panama Canal, the primary attraction in the country, receives just under a million visitors a year.

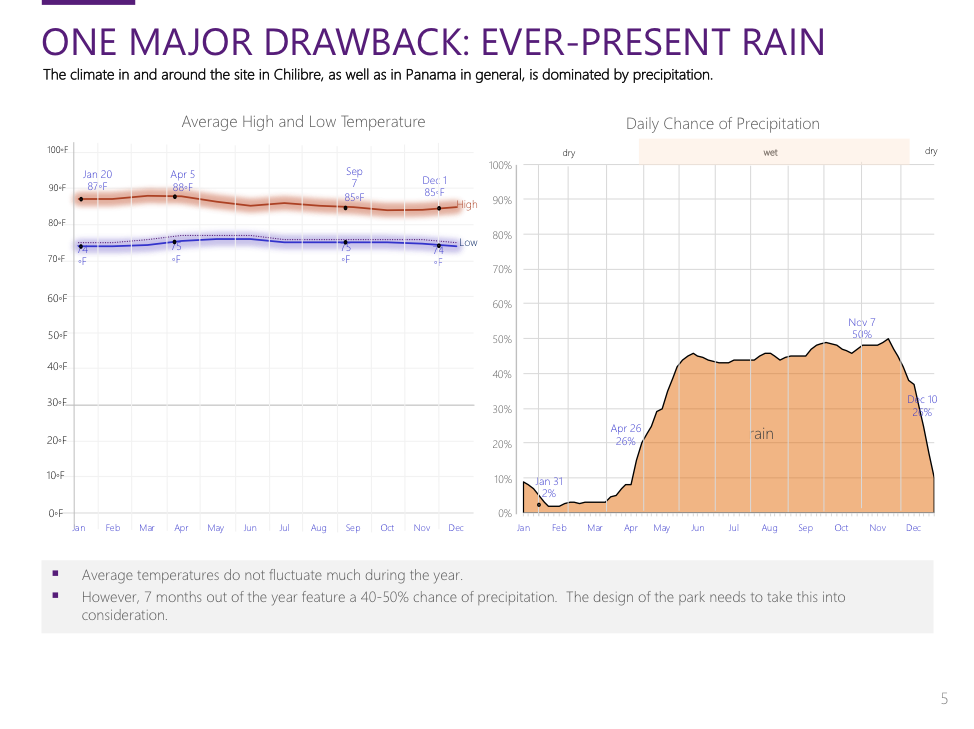

4. The last major factor that cannot be ignored is Panama’s climate. Precipitation is high, with probabilities of rain of between 45-50% for the majority of the year.

Conceptualization

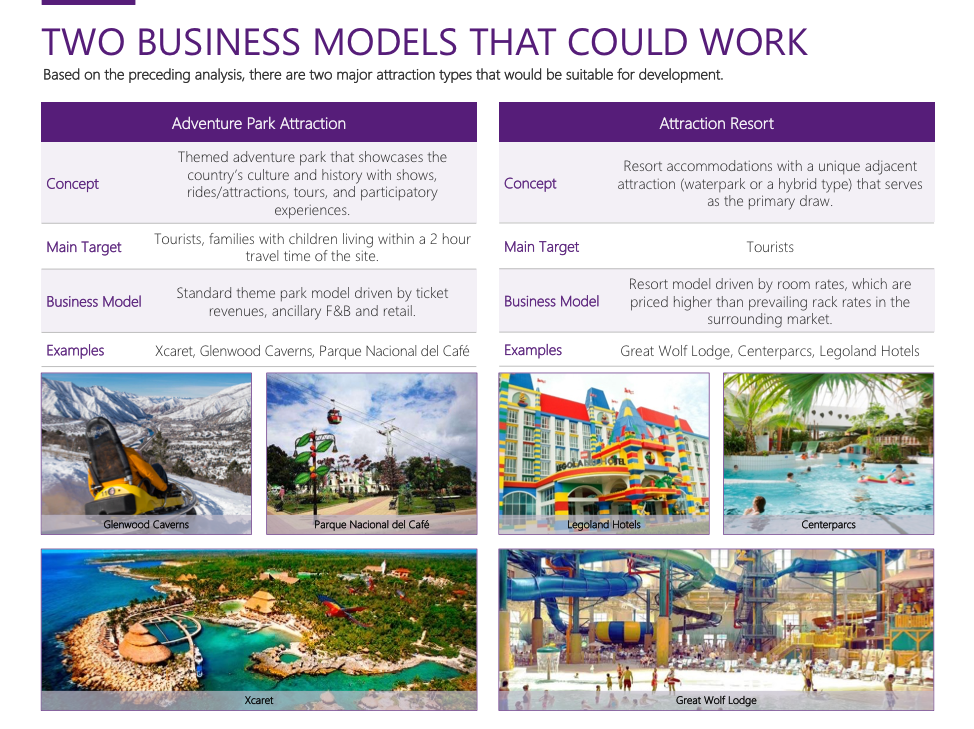

Given the market size, competitive context, and climate, we determined two potential land uses that would represent the highest probability of success for the project.

1. An adventure park drawing on the climate, topography, and history of Panama. Such attractions are light on the hardware, minimizing the huge investment costs of typical theme parks.

2. An attraction-driven resort targeting tourists. Such attractions derive their revenues from higher-than-average occupancies and average room rates, which justify the investment in a larger than normal amenity, most typically in the form of a waterpark.

Concept 1: Adventure Park

1. To reiterate, the market is quite limited in Panama. The overnight tourist population outnumbers qualified residents. At moderate penetration rates, the market likely would not support a theme park of over 1.5 million in annual visitation.

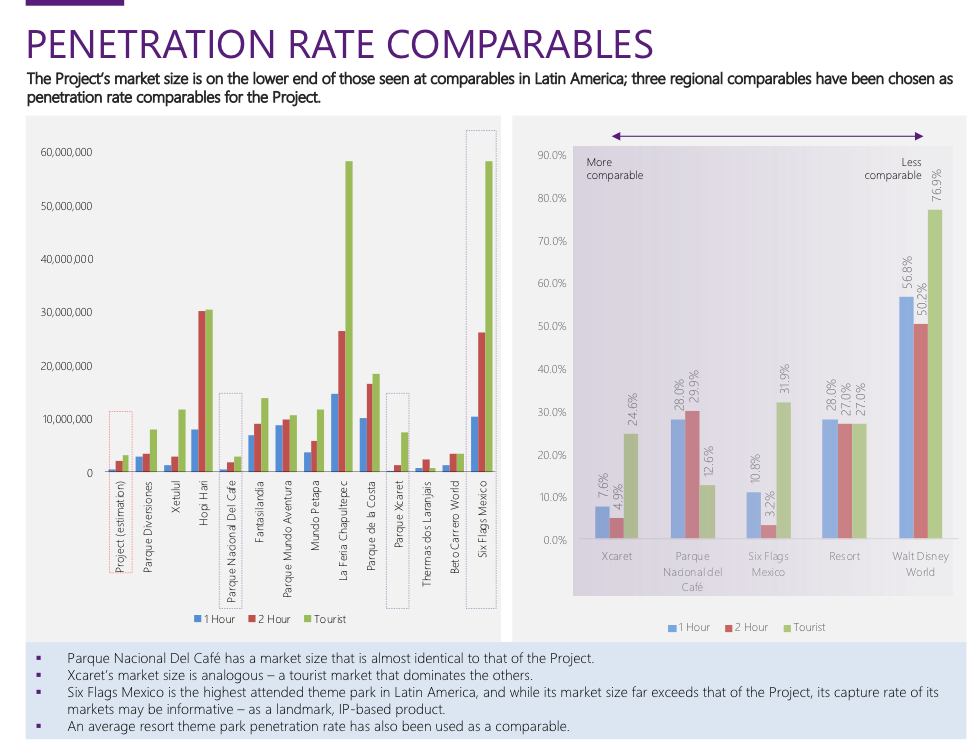

2. We use weighted average penetration rates to derive this figure. Xcaret (due to concept similarity) and Parque Nacional del Cafe (due to market size similarity) are the concepts with the highest degree of comparability. For more details on the analysis, please refer to the in-depth report.

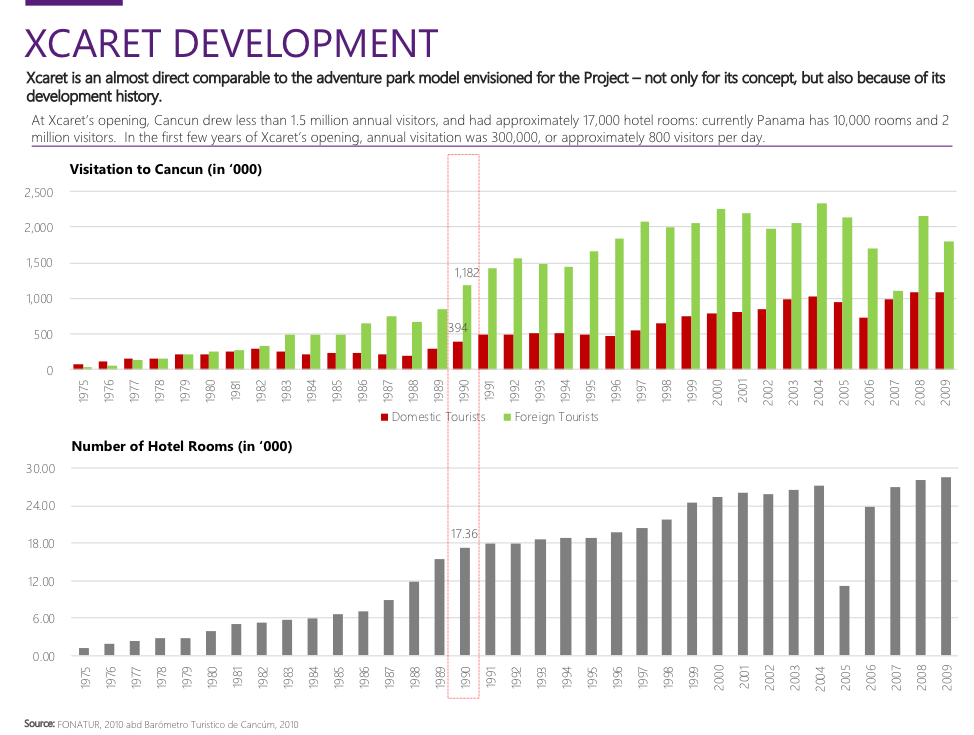

3. The key comparable for an adventure park in Latin America is Xcaret. Developed by the Grupo Xcaret over a period of 30 years, the master plan includes several attractions and resort accommodations, and clearly demonstrates how a phased, sustained vision can play out over time, both complementing and benefitting from the development of Cancun in general.

Panama’s current market situation is analogous to Cancun’s when Xcaret was developed; such long-term thinking and the execution of a vision over time would be required in Panama’s case.

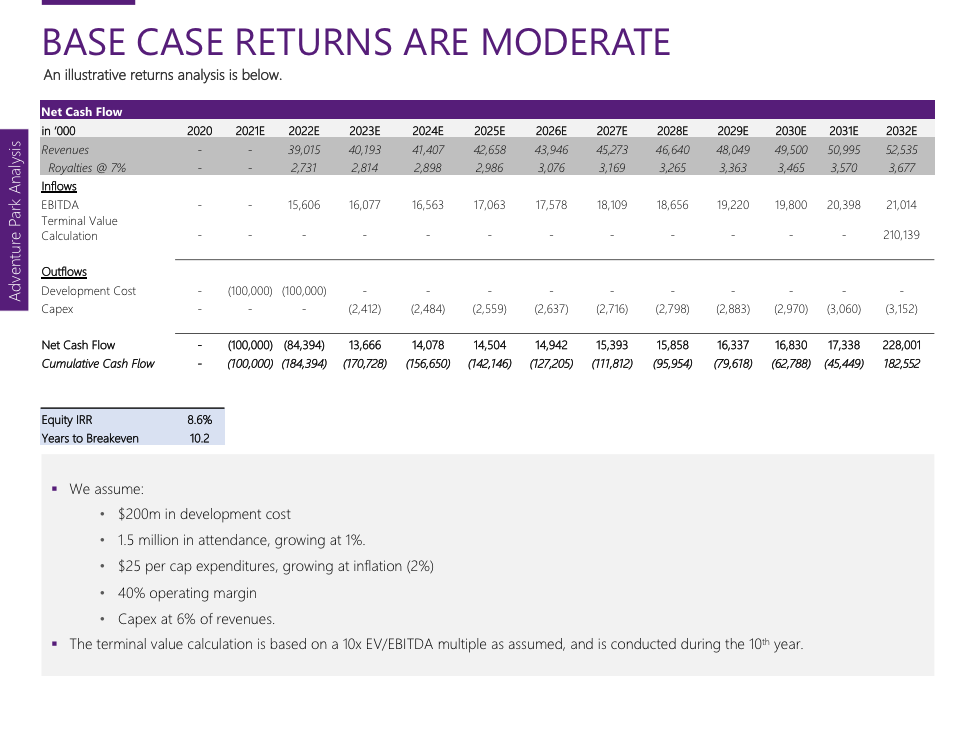

4. To conclude, the key question is whether an attraction of some scale could be constructed for $200 million or less, which represented the maximum investment to achieve the targeted return figure of 10%. As the financing required rates of return, and status of potential government funding was uncertain, we advised Isthmian Development Advisers/NSB Caribe to use this figure as a planning number.

A scenario analysis is available in the full report.

Concept 2: Waterpark Hotel

Concept 2: Waterpark Hotel

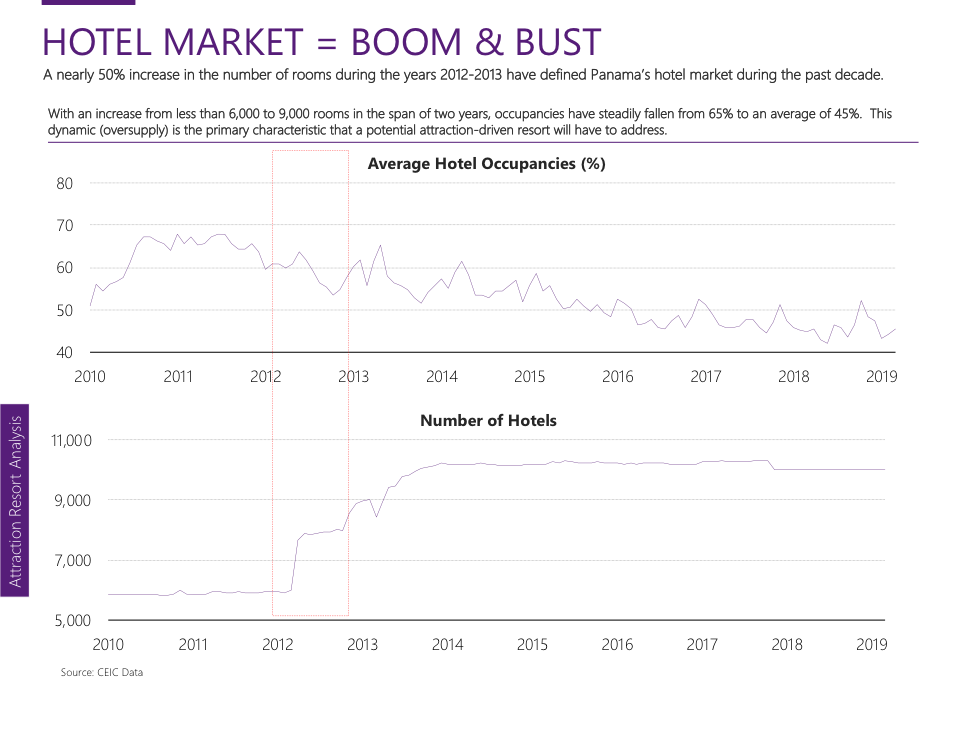

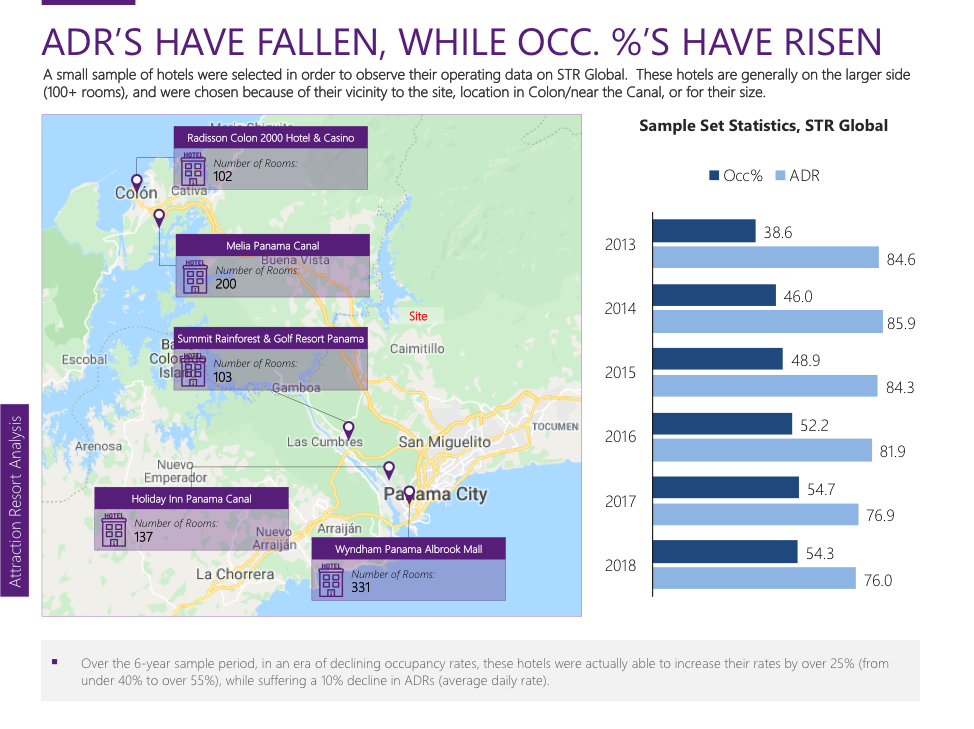

1. First, for some context. The hotel market is Panama is defined by the huge boom that took place in the 2011 period, and which to a certain extent is still playing out. This has depressed occupancies, although room rates have crept up over time.

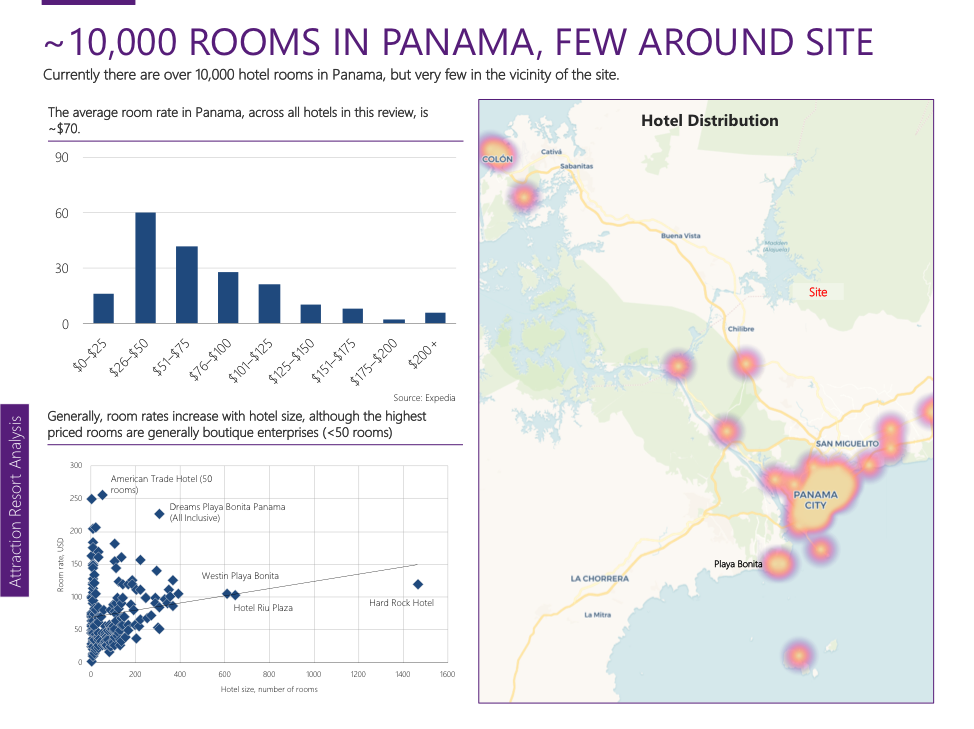

2. While there are 10,000 hotel rooms in Panama, very few were present in and around the site. Moreover, listed room rates averaged $70. For the hotels that we believed to be the closest in comparability to the project, occupancies averaged a barely break-even 50%, with room rates in the $80 range.

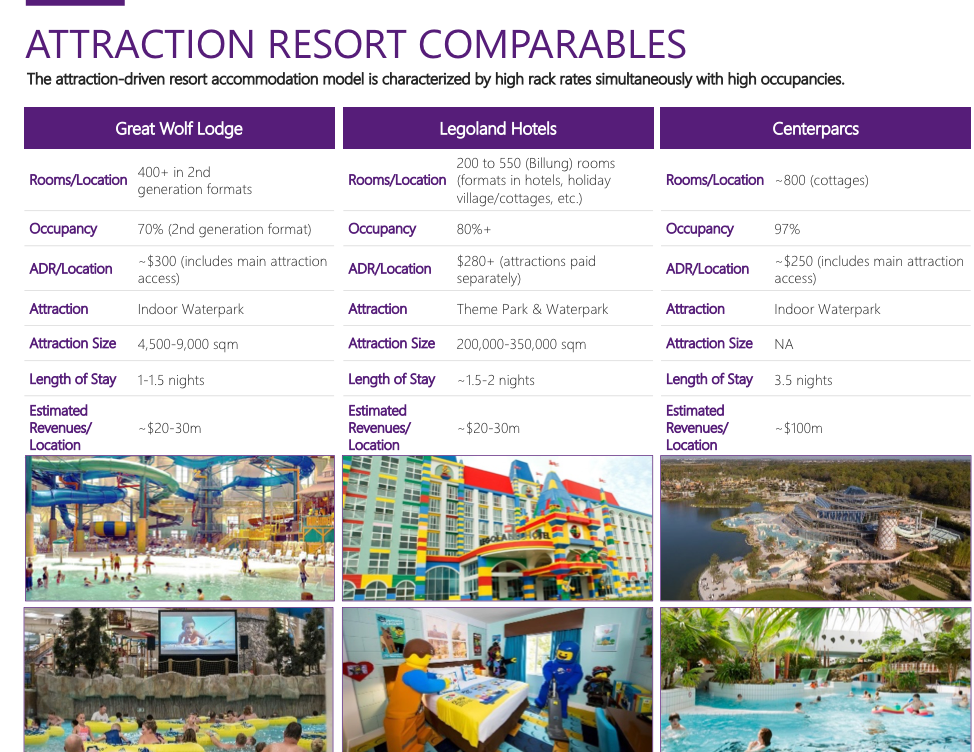

3. The best comps for waterpark & themed hotels are the Great Wolf Lodge, Centerparcs, and Legoland operations. These imply that occupancies need to be much higher than the local average, as do ADRs.

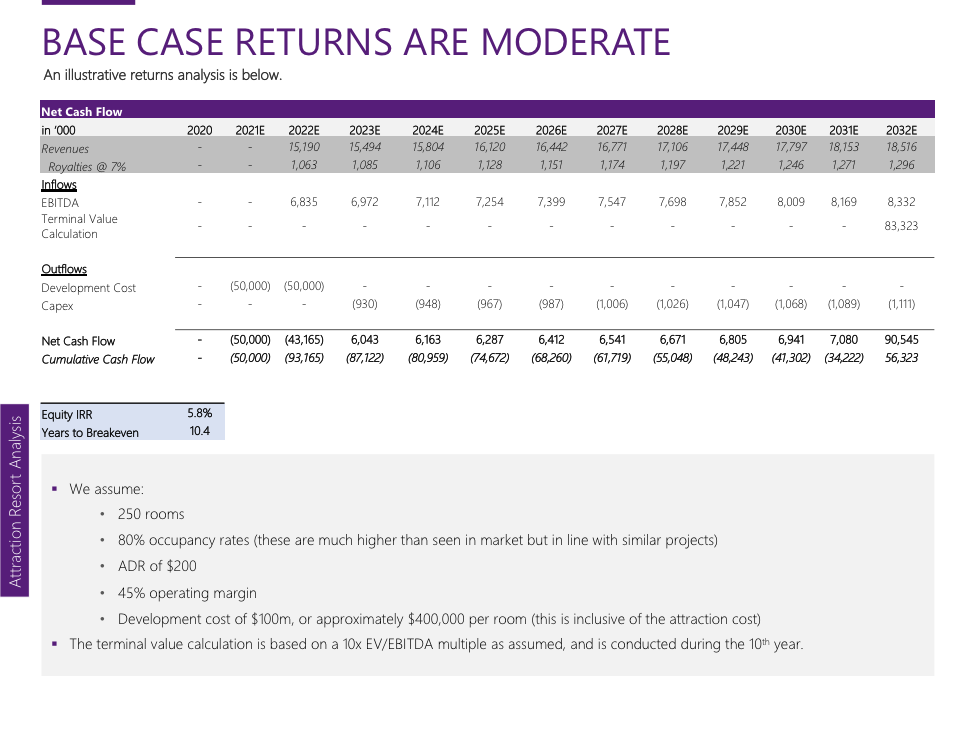

4. Given the state of the market, the investment cost of the resort hotel would need to be less than $100 million to make economic sense. Financing options, including those from the government, were also discussed with NSB Caribe.

A base case scenario as seen below, which is a 250 room operation at an 80% occupancy rate, and $200 ADR is in line with international comparables, but far exceeds the average performance of local ones. Sizing and pricing the project this large/high would represent a risk, and this was further detailed in the scenario analysis (available in the full report).

The full report is available for download here.