Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

On the news of the potential merger between Six Flags and Cedar Fair, we thought it might be worthwhile to look back at their history and consider their place in the attractions landscape. With their thrill park offerings, both chains occupy a distinct niche within the theme park industry. Both chains are also characterized by a reliance on deal-making.

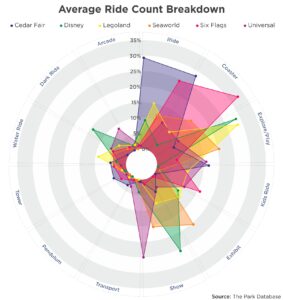

Today, Cedar Fair and Six Flags are the two largest regional theme park operators (by park count) in North America. In positioning and consumer perception, their parks are distinctly in the thrill park/ride park category, consisting of roller coasters, flyers, swings, and other mechanical amusements.

It might be easier to understand what they are, by striking out what they’re not: they’re not megaparks along the lines of Disney and Universal Studios, both of which have taken a decidedly cinematic, media-based turn in recent decades. Contrast them also to the aquatic adventures of SeaWorld, or the toy brick-infused playgrounds at Legoland.

The Six Flags and Cedar Fair archetype is “Purveyor of G-forces,” rather than of immersive lands with brands and characters that evoke deep emotional attachment (e.g. Marvel, Star Wars, Harry Potter, Ninjago). Can you name a Six Flags or Cedar Fair “character”?

What they offer is a thrill/ride park experience, and it’s a tried-and-tested formula, one that harkens back to the earliest days of the amusement park industry. One view of Cedar Fair and Six Flags is as the torchbearers of this century-old legacy.

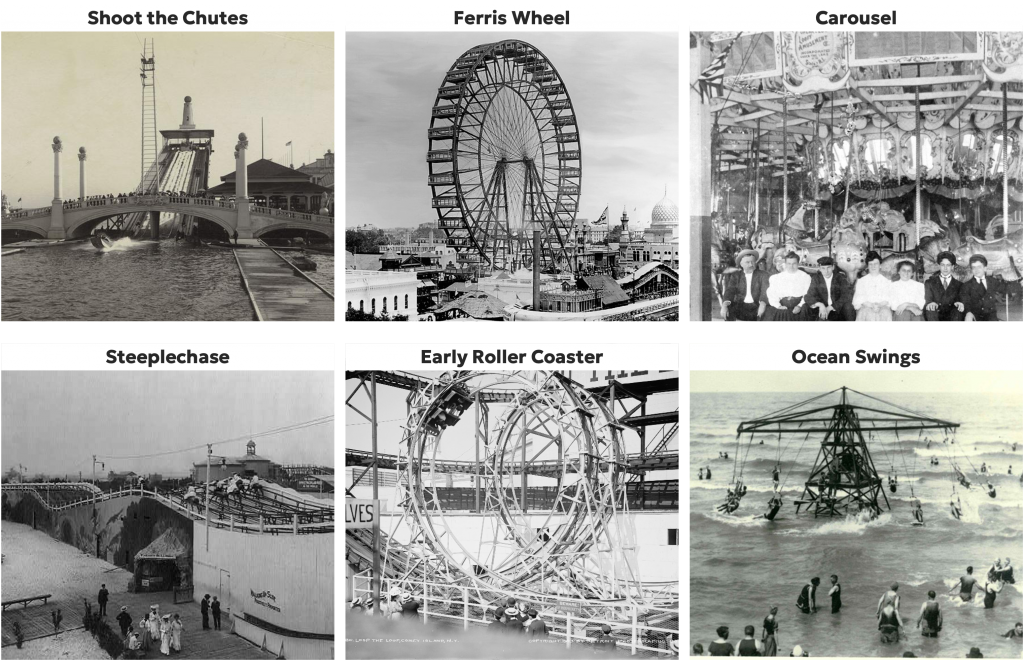

Their core experience isn’t much different from the offering of the earliest American amusement parks at the turn of the 20th century, when ferris wheels, coasters, carousels, and flume rides were first invented. The mainstays of the theme park culinary experience, such as ice cream and hot dogs, debuted during the early 1900s. Shows and exhibits were a core part of the trolley parks, boardwalks, and amusement park experience back then too. And before waterparks and water slides, there were salt water pools, bathing ponds, and ocean swings.

The History of Ride Parks

Sure, the coasters have gotten faster, the towers have gotten taller, and parks have gotten bigger, but the core experience is much the same. Expectedly so: Cedar Point, from which Cedar Fair takes its name, is the oldest extant park in the United States. The chain also includes Dorney Park, a trolley park built in 1884. Similarly, Six Flags New England started life as a picnic grove at the turn of the 19th century, before being converted into an amusement park in 1912.

These are among the few amusement parks of that golden era that exist today. Electrification, increasing leisure time, and a spirit of innovation powered an explosion of amusement parks in all sorts of creative manifestations. In those early days of amusement parks, there were no rules, and the “amusements” rolled out in these projects took forms unimaginable today – some rides’ sole purpose was to fling people off of them, without seat belts or harnesses. Casinos, dance pavilions, and beer halls were juxtaposed next to rides. Shows made frequent use of animal cruelty, while human zoos of “exotic” people featured prominently. In parks like Steeplechase Park, staff used cattle prods to literally shock visitors.

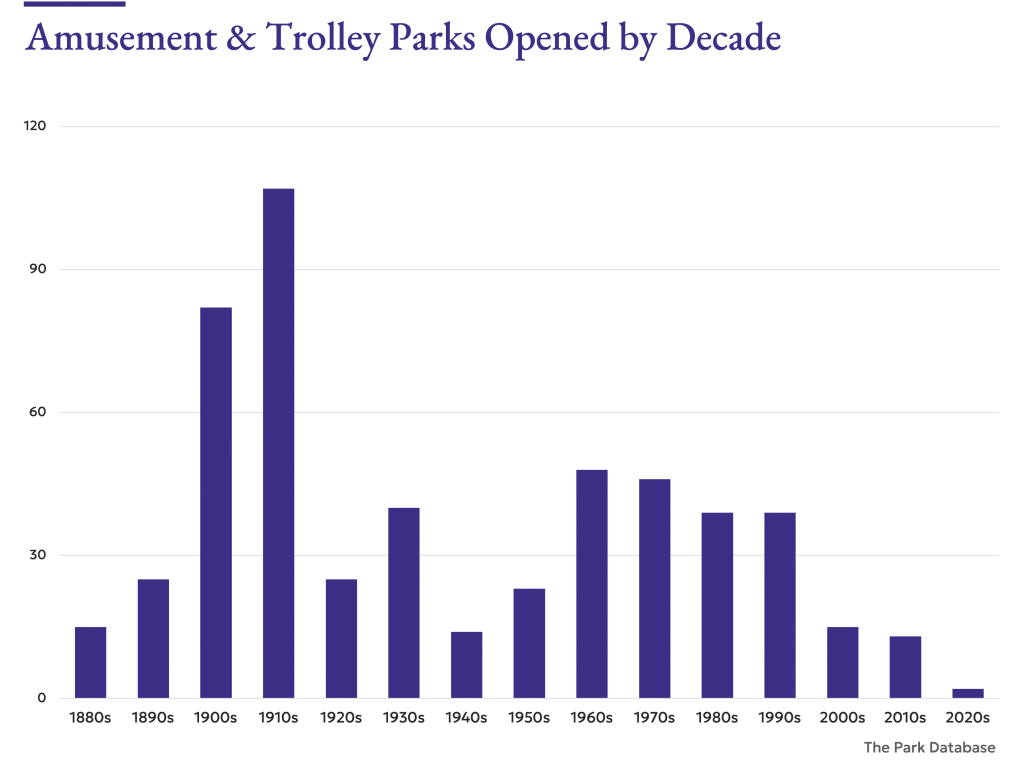

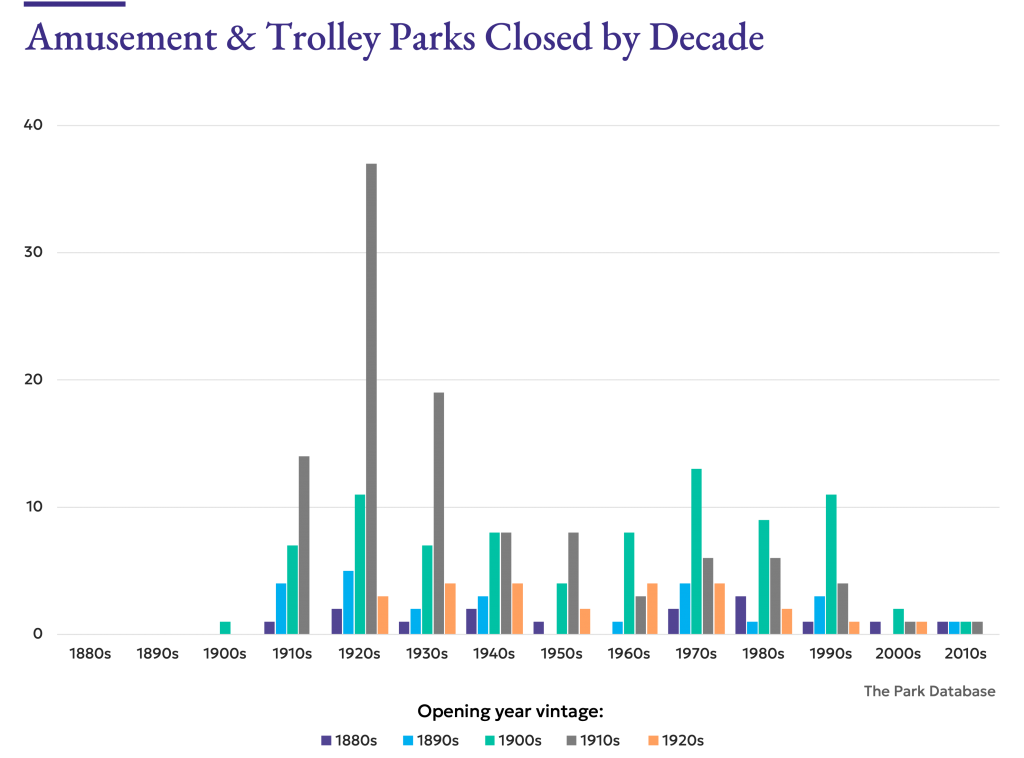

In 1905, a “mania” ensued as over 1,500 amusement parks dotted the fairgrounds, picnic groves, beachside resorts, and hills of America. But after a worldwide depression and world war, many of these parks had outlived their appeal. Economic conditions, shifting population centers, and changing consumer tastes brought on a mass extinction of these amusement parks. Many simply burned down.

This cleared the slate for a second American amusement park boom during the post-war 1950s to 1970s. Led by Disney, these projects now had a new name: “theme parks”. Taking advantage of a growing population and low-priced land, today’s major theme park chains were launched during this time.

Disneyland opened in 1955; Universal Studios Hollywood started as a tour in 1964, the same year as SeaWorld. The entity that became Six Flags opened the first of its parks in the 1960s; Cedar Fair was created in a merger between Cedar Point and newly-built Valleyfair in 1978. The first waterparks were also opened during this era.

Stagnation or Stability?

Ride parks are built on the DNA of an attraction type that’s more than 100 years old. And as analysts of this industry, it would be irresponsible not to consider the possibility that perhaps for the ride/thrill park product, this second boom may also be in its waning phase.

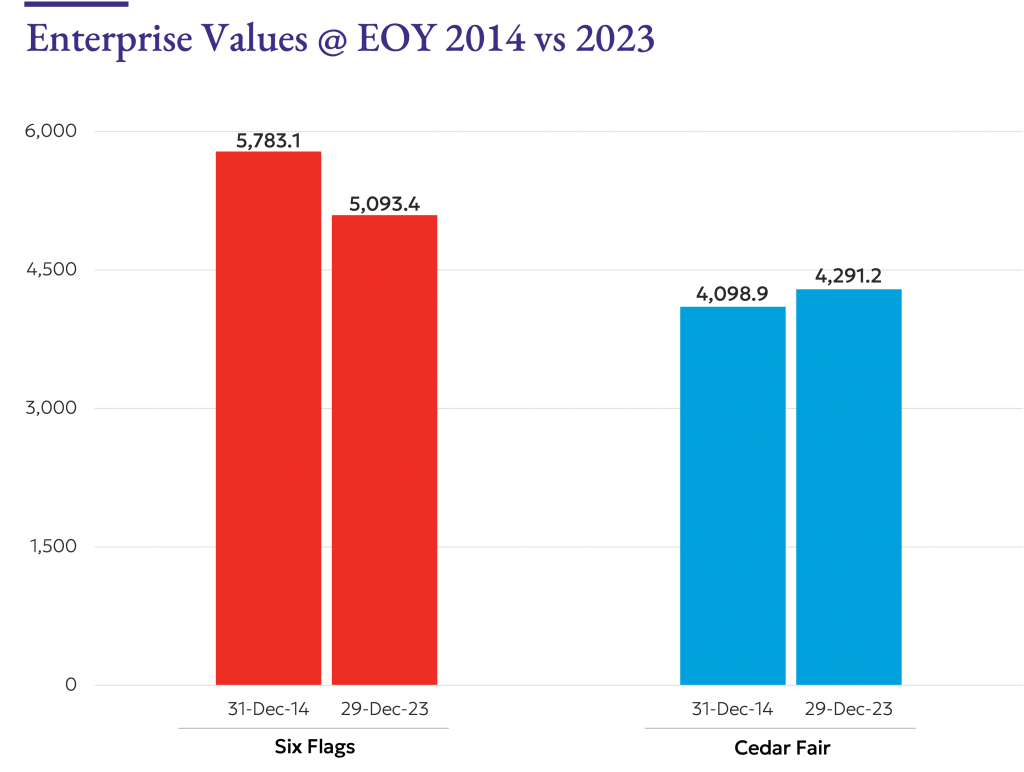

Certainly the financials might attest to this. Attendance to both chains has been lagging, and for the past ten years, the market has assigned a stagnant value to their operations. The enterprise value of Six Flags was nearly $6 billion in 2014-2015; at the end of 2023 it was $5 billion. Cedar Fair’s was little over $4 billion in 2014-2015; it was a little over $4 billion in 2024.

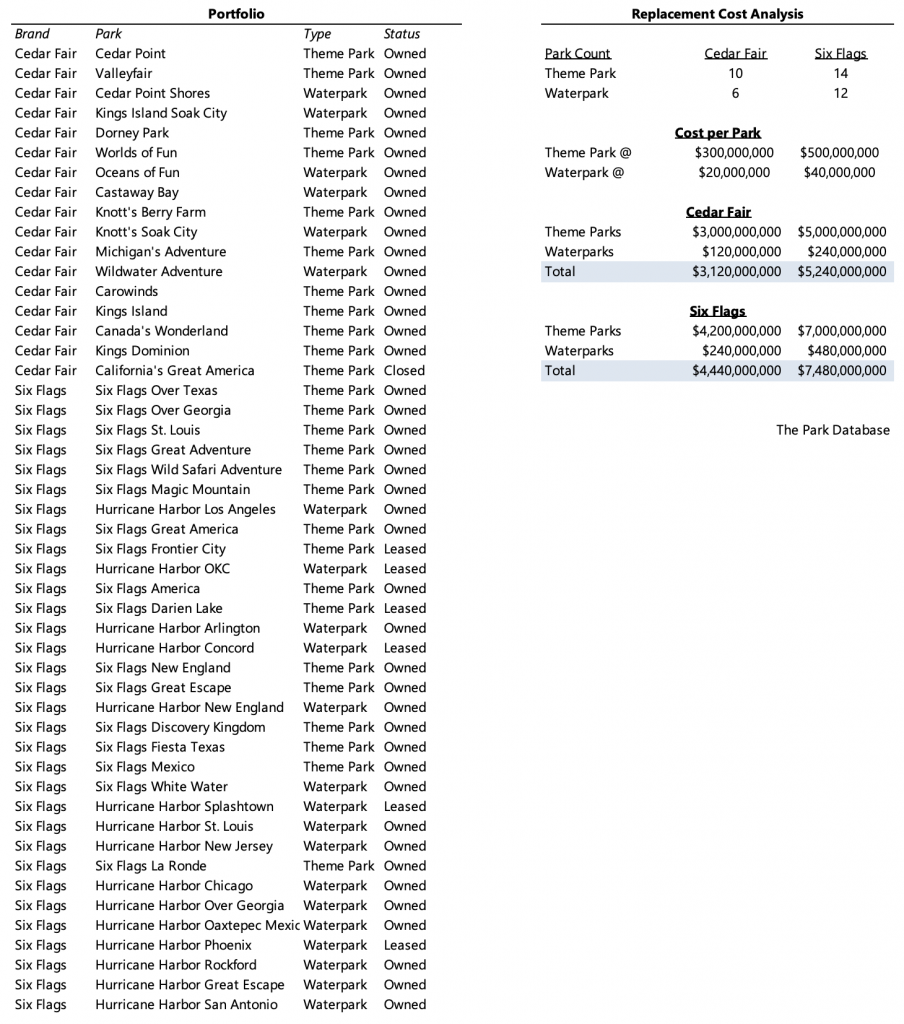

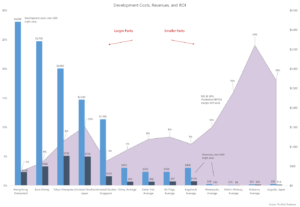

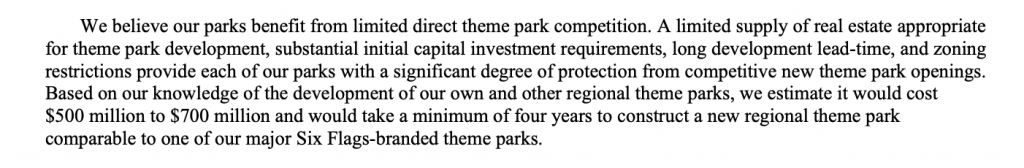

Both chains are almost certainly trading for below their replacement values. Current valuations imply a value per theme park of between $300m to $400m, including land costs – which is likely unachievable in current conditions. In 2022, Six Flags estimated a replacement cost of $500m to $700m for its parks. Depending on land costs, this may vary widely, but based on our knowledge of the industry the general magnitude is correct – it would be difficult to replace any major theme park for less than $400 million. (This can of course be verified using our investment cost tracker).

So what does it mean if the cost of replicating the Six Flags or Cedar Fair portfolios is higher than their values? It would seem to deter any future development of theme parks in the markets they operate in. It would seem to suggest that these parks, at least in their current form, are in an oversupplied or overcapacity situation.

Perhaps an analogy would be to something like a coal-fired power plant. No one will be building any more, but as a cash-flow generating asset, their owners have an interest in maintaining it until the end of its useful life.

Deals as a Strategy?

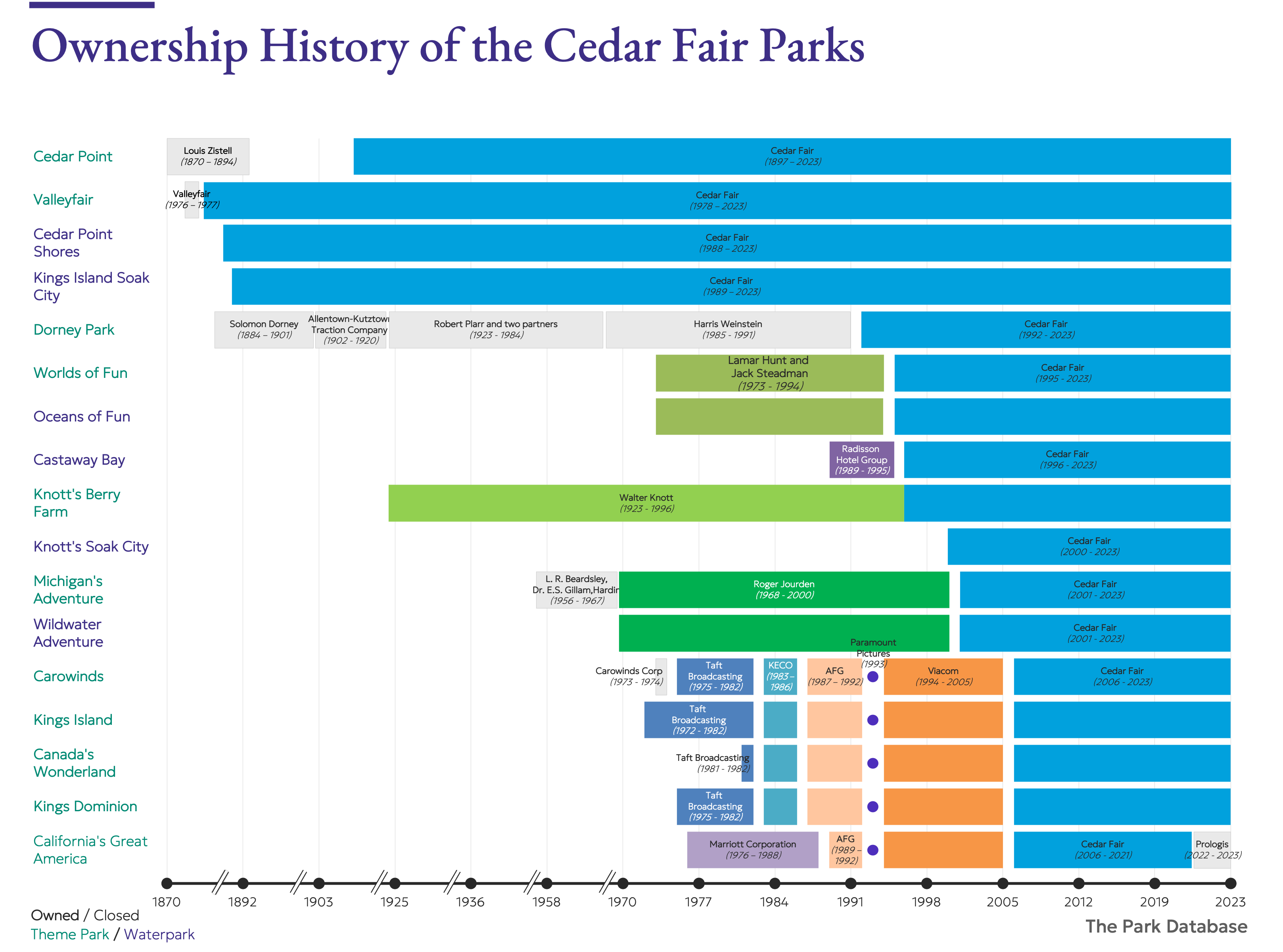

This is likely no surprise to management at either chain. For decades, their growth strategies have been that of expansion and acquisition, rather than on the repositioning or re-imagining of the core ride park experience. The propensity for deal-making at either chain has been so high that it’s inextricable from any analysis of their operations.

One could interpret the inclination to do deals as the cause of their distinctive positioning: with so many operations across different geographies, markets, and previous owners, what else could have resulted but a portfolio of ride parks – the most basic, tried-and-tested assemblage of classic rides, with a minimum of operational complexity?

One could also feasibly argue that perhaps it was the nature of thrill parks, for reasons including but not limited to seasonality (closed months out of the year), high capex requirements (brand new novel coasters or rides, each $10-30m), and changing consumer tastes, that the only way for them to survive, in the aggregate, was to expand and acquire others over time.

Cedar Fair

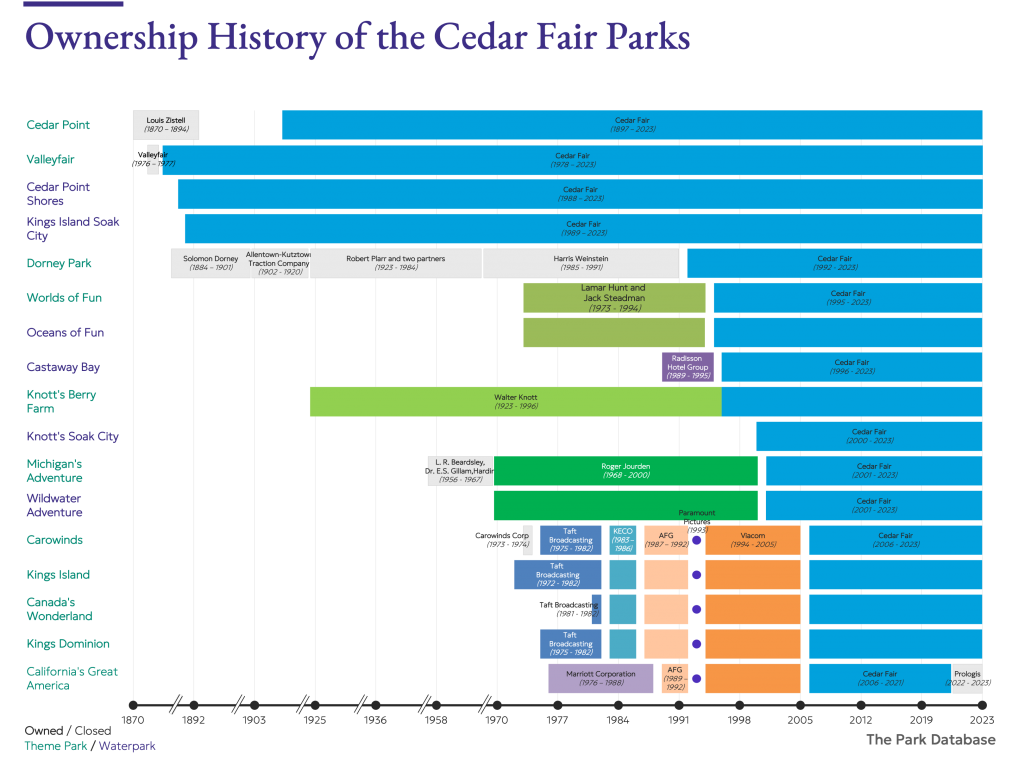

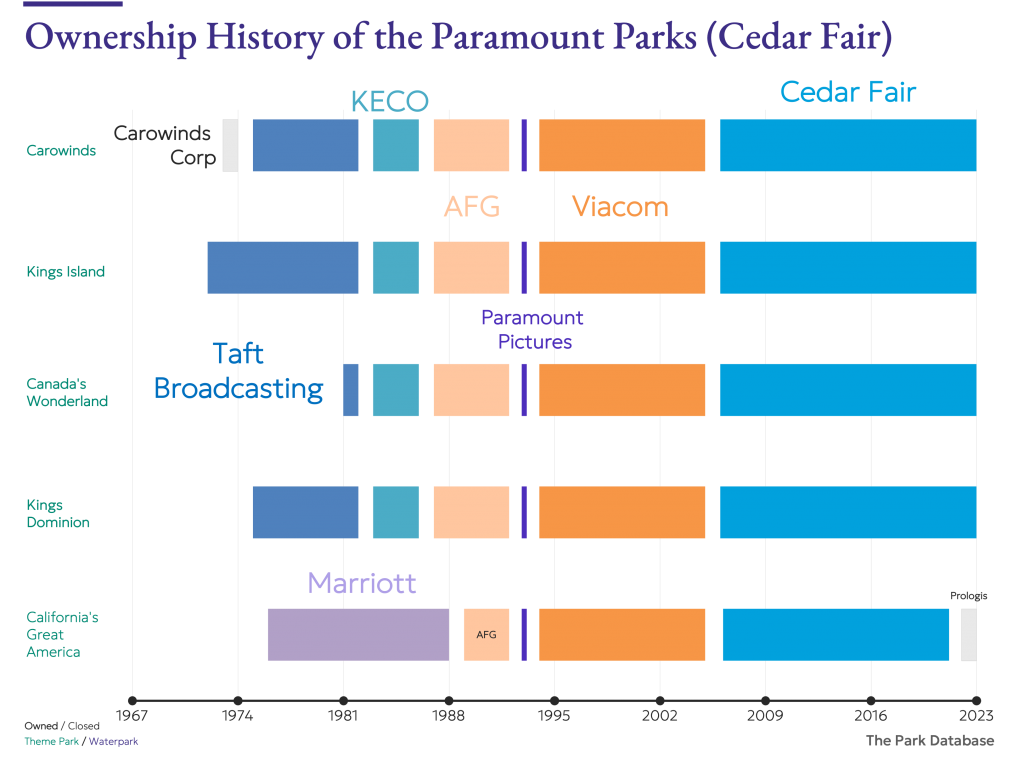

Whatever it was, the history of both chains has been highly transactional. Over the course of a decade from 1995 to 2006, Cedar Fair tripled the size of its portfolio by adding Dorney Park, Worlds of Fun and accompanying waterpark, and Knott’s Berry Farm in Orange County, which had predated even Disneyland. It further added Michigan’s Adventure and its adjacent waterpark, while simultaneously opening other waterparks. Then in 2006, it purchased the five-park portfolio of Paramount Parks (then owned by Viacom).

Six Flags

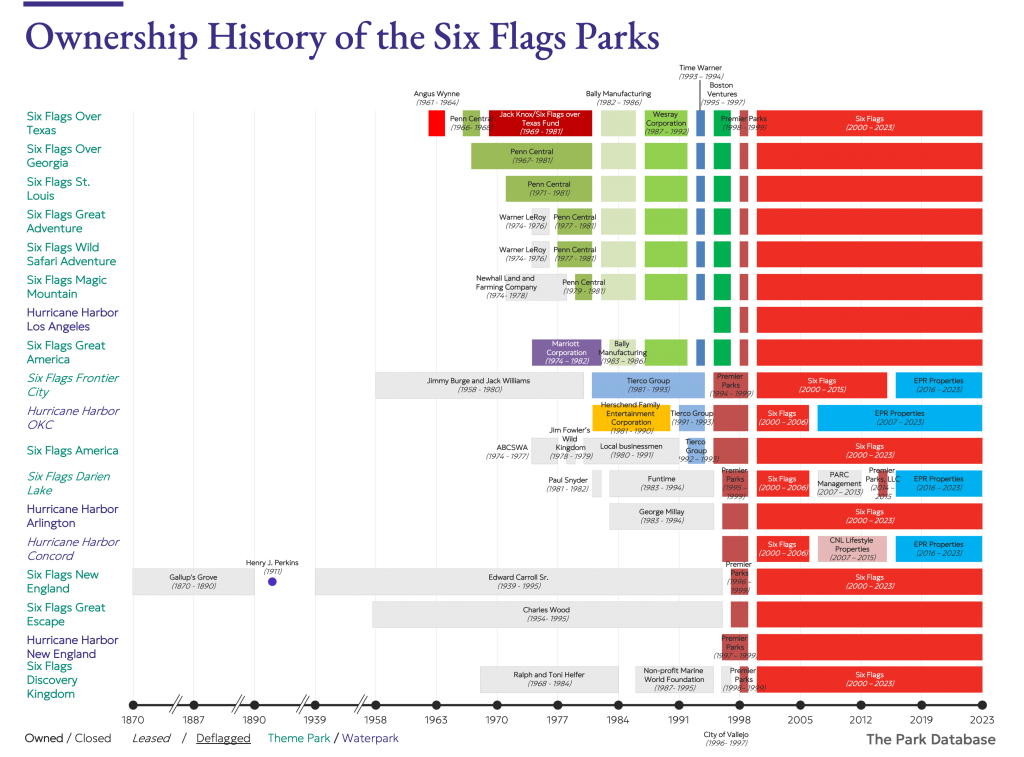

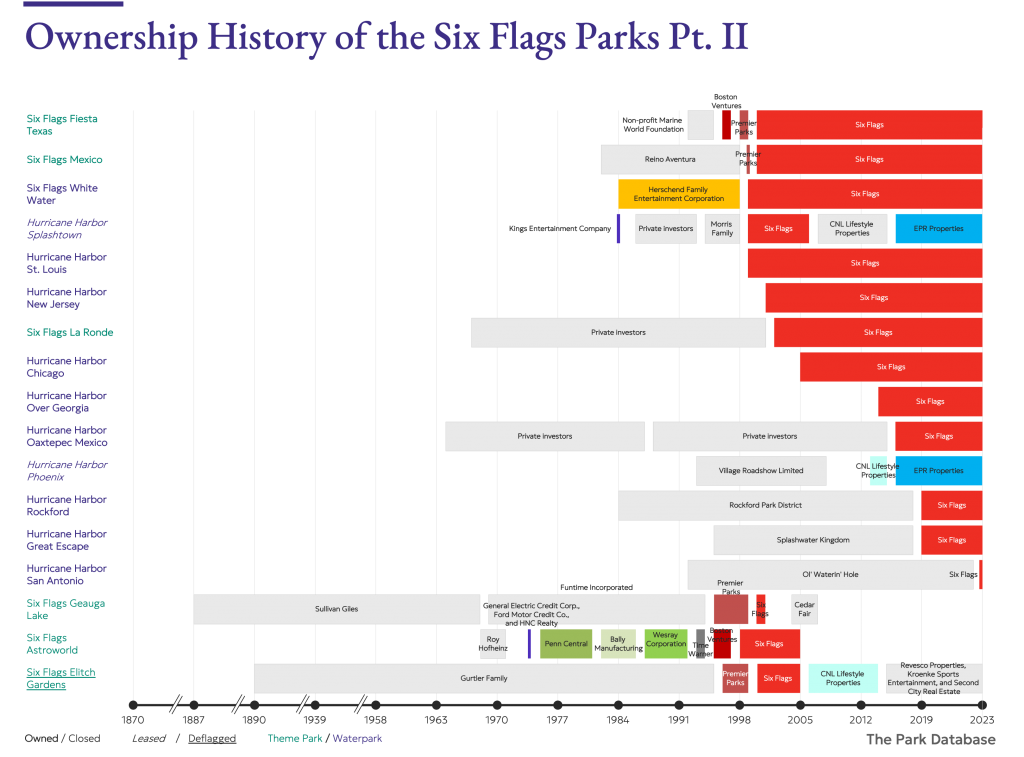

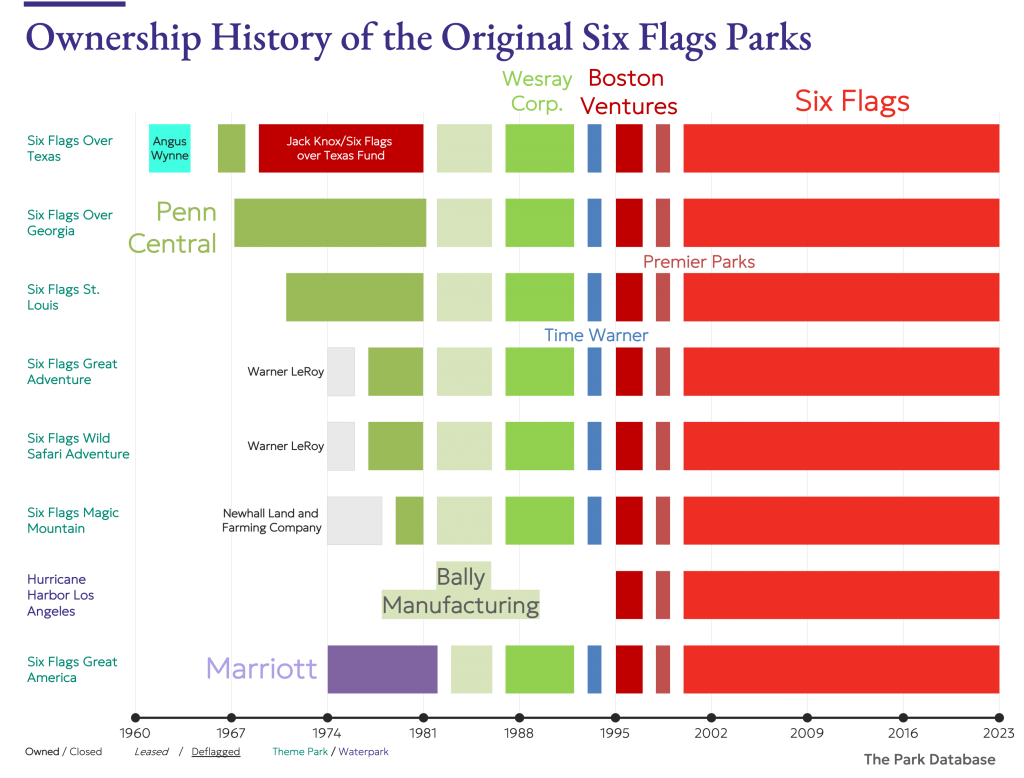

The current state of Six Flags was a result of even more deal-making. The original Six Flags opened in Arlington, Texas, in 1961, and was subsequently purchased by Penn Central, which was looking to diversify beyond its railroad revenues. After opening parks in Georgia and St. Louis, the chain purchased three more during the 1960s before being flipped among various owners for the next twenty years.

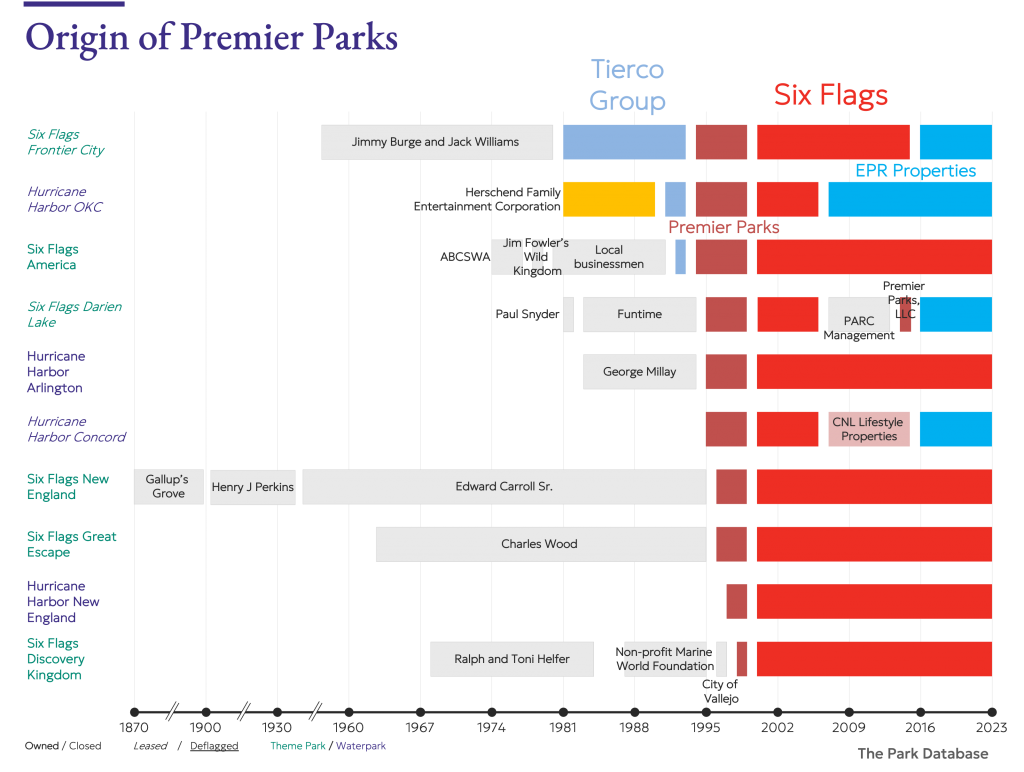

Six Flags then took its final form by combining itself with another entity. In the center of the United States, a company named Tierco had originally bought the Oklahoma City-based Frontier City theme park in order to redevelop the land. When the plans fell through, it continued to operate Frontier City. It found the venture so profitable it went on to add the White Water waterpark (Hurricane Harbor Oklahoma City) and Wild World theme park (Six Flags America) to its portfolio.

The company renamed itself Premier Parks, and continued its acquisitions spree. By 1997, Premier Parks had nearly 10 operations, and doubled its size the following year by acquiring the Six Flags portfolio, then owned by Boston Ventures and Time Warner. In 2000, all parks under its management began operating under the Six Flags name. It continued to add and open new parks for the next 20 years.

Such expansion led to a lack of continuity and coherent long-term strategy – or was M&A their strategy all along?

Collectively, the parks went through multiple changes of owners, from private funds, governments, amusement operators, or the original founding entrepreneurs, with the strategy changing every time. The original Six Flags portfolio had gone through five different corporate owners by the time Premier Parks acquired them: Penn Central (a railroad), to Bally Manufacturing (who had stocked the parks with its arcade machines), to Wesray (a buyout fund), to Time Warner (media conglomerate), before it too sold a majority stake to Boston Ventures, a private fund. Expanding too fast spelled trouble for Six Flags by the end of the 1990s. Facing a shareholder revolt and high debt loads, the chain went bankrupt in 2009.

Such flipping of ownership (and motivations) was mirrored at Cedar Fair. The chain’s Viacom portfolio had been variously owned by Taft Broadcasting (who had themed the parks with Hanna-Barbera content – e.g., the Flintstones), Kings Entertainment Corporation (who took control via management buyout), American Financial Group, and then finally Paramount Pictures, who attempted to return the park to its themed roots by adding Top Gun, Scooby Doo, Tomb Raider, and the Italian Job-themed rides. It maintained control over the park for only a year before Viacom acquired control of Paramount Pictures, although the parks continued to be branded under the Paramount name.

Then there were the parks that had originally been developed by Marriott (yes, the hotel chain), which in the 1970s joined the growing theme park trend by developing the theme parks that eventually became California’s Great America (Cedar Fair, via Paramount) and Six Flags Great America. Amidst this, there was even an iconic park – Geauga Lake – that traded hands between Cedar Fair and Six Flags.

We are aware that these diagrams do not show the totality of the picture. Six Flags, for example, outright abandoned some parks (e.g. New Orleans) and at one point had European operations that it sold off during its debt-related troubles.

Further Contrasts

While such M&A resulted in incremental income, it didn’t necessarily translate into outperformance of their existing operations over the long-term. A quick look at the Southern California market illustrates this.

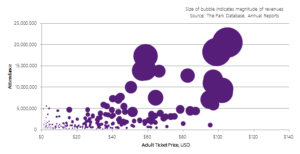

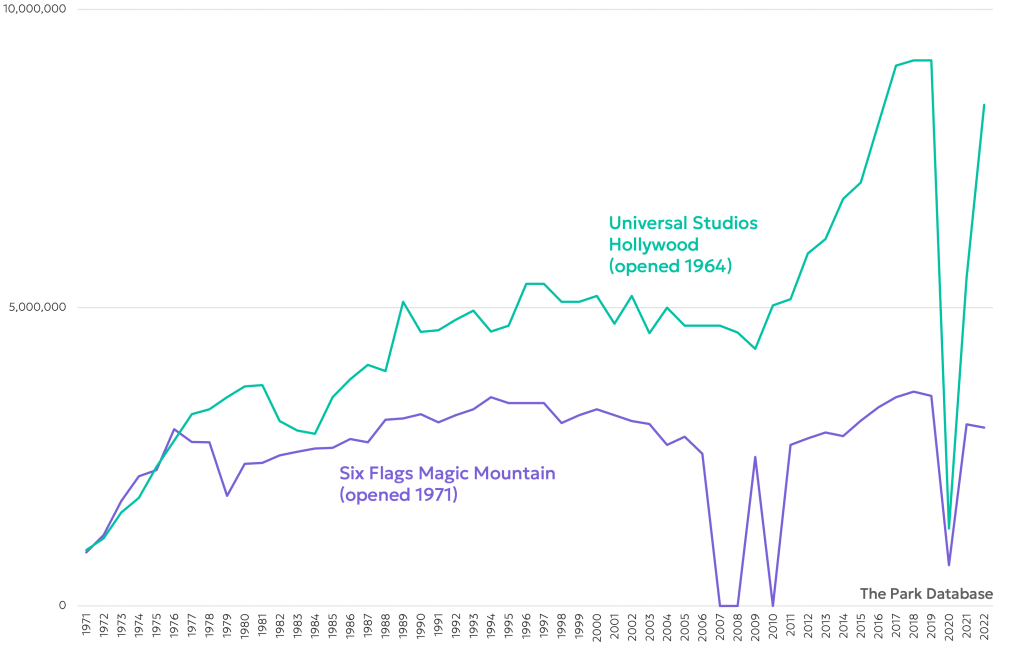

In 1971, Six Flags Magic Mountain opened to an annual attendance of 900,000. Not too far away, Universal Studios Hollywood recorded a similar visitation level – it had been only seven years since it had opened.

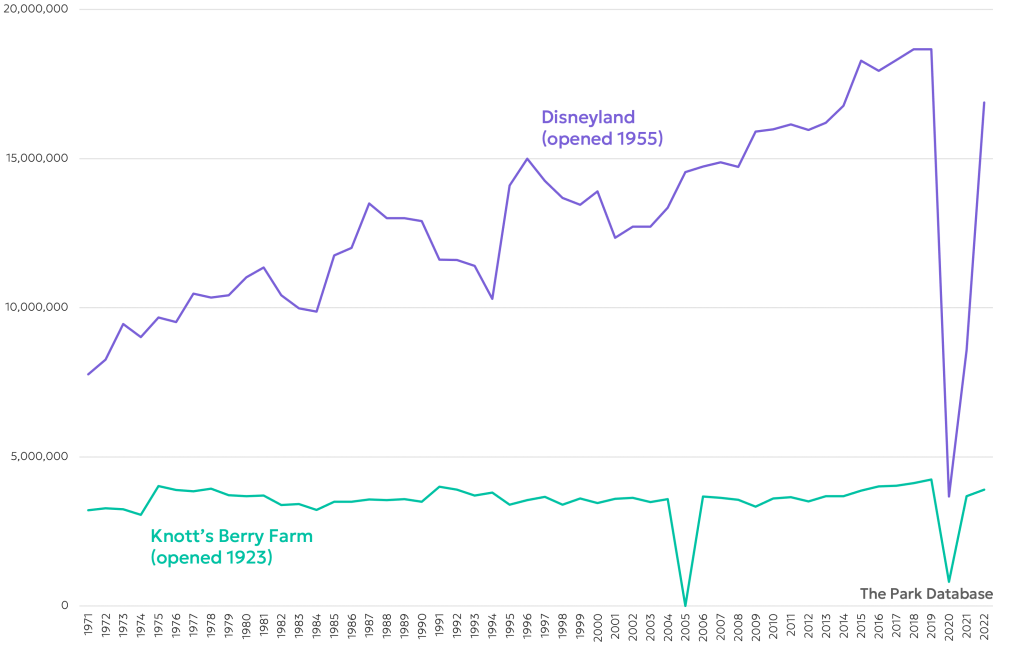

But the largest attractions in the Southland during that year were in Orange County, where Disneyland recorded visitation of nearly 8 million, while Knott’s Berry Farm (Cedar Fair) entertained over 3 million guests.

The diverging fate of these parks over the next 50 years is indicative. Disneyland doubled its attendance, to nearly 17 million, but Knott’s Berry Farm grew its visitation by barely 25%. Universal Studios Hollywood’s attendance grew by nearly 8x; Magic Mountain grew, too, but by 3x.

What are we to make of this? On one hand, you could make the case that with such a short average ownership tenure, the parks owned by Cedar Fair and Six Flags parks have never had the chance to decently compound their performance over the long-term. Or as an extension of this point, perhaps it’s been an issue of too many parks, too soon.

After all, Universal Studios’ corporate history has similarly been marked by a frequent ownership change – from MCA and Matsushita, to Seagram, Vivendi, and Comcast. But Universal Studios only opened a second park 25 years after its first, and has undertaken subsequent projects at average intervals of 10 years between parks. The chain has a similar age to that of Six Flags – but the latter has nearly 30 operations to Universal’s 6.

The Media Strategy

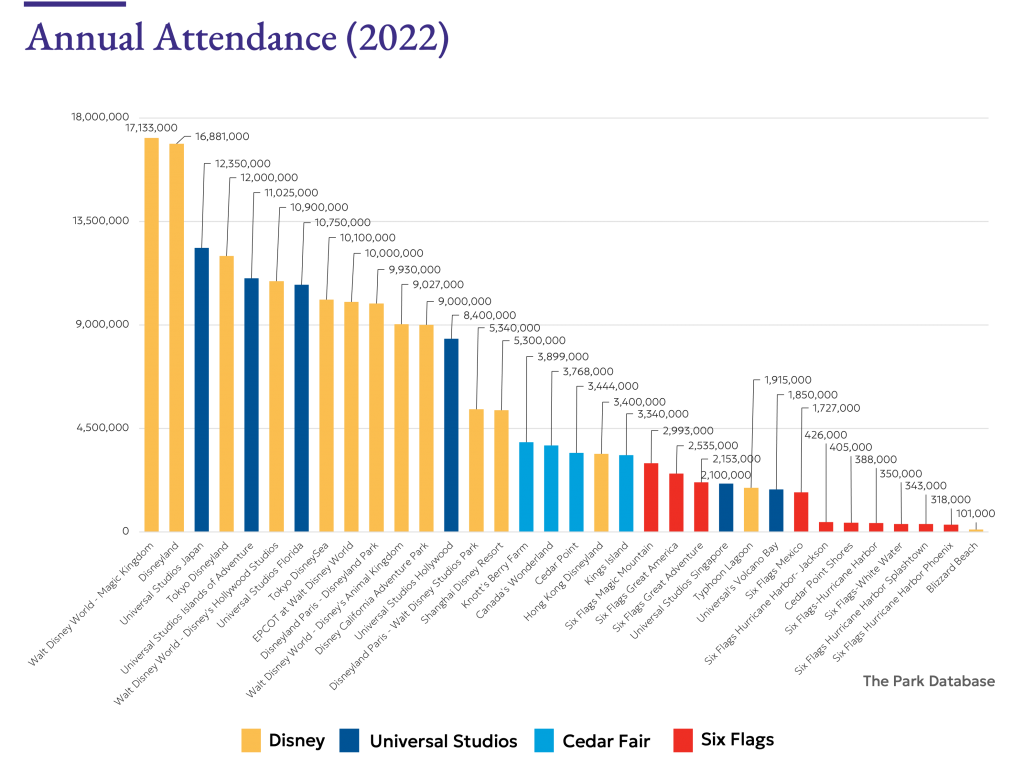

Dig deeper, though, and there may also be something fundamental in the difference between a ride park and the theme parks represented by Disney and Universal. From a similar starting point, Universal Studios has leapfrogged the ride park chains in visitation and revenues. On the other hand, it almost appears as if there’s a natural limit to ride park attendance in North America. None of the parks owned by Cedar Fair or Six Flags breaks the 4-5 million visitor mark. Attendance has been steady, almost asymptotic.

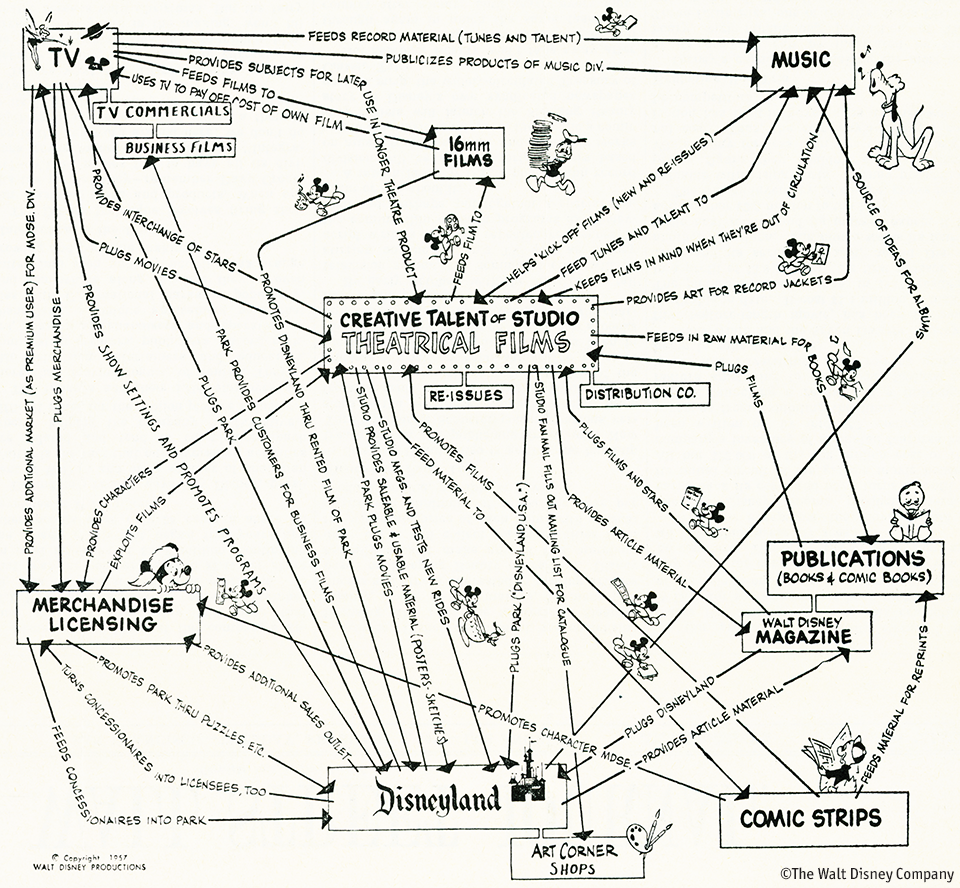

What’s the difference? For one, both Universal Pictures and Disney have been owned (mostly) by deep-pocketed media conglomerates for whom theme parks have been just another marketing outlet for their media properties – i.e., content. From the beginning, Walt Disney envisioned Disneyland as an outlet for cross-promotion of its television programs, movies, and merchandise. The “content” – the stories and characters – has provided guests with a sense of emotional resonance and attachment, one that is evidenced by ever-increasing attendance and high spending.

Since theme parks are a complementary, synergistic business to these media conglomerates, by definition it means that theme parks are not their only business. The reasons to own theme parks, for Disney and Universal Studios, are not solely financial. Lean, unprofitable years have been tolerated without jettisoning the parks responsible for them. I.e., Disneyland Paris has rarely turned a profit for the last 30 years. Hong Kong Disneyland has fared the same since its opening twenty years ago. And when Disneyland Shanghai merely broke-even in its first year of operations, it was heralded as an achievement for the ages.

Both Six Flags and Cedar Fair, for a time, flirted with the possibility of pursuing this kind of strategy. Six Flags was majority-owned by Time Warner for a time. A substantial portion of the Cedar Fair portfolio was held by Paramount Pictures and Viacom, and before them, by Taft Broadcasting. Could a Hanna-Barbera- or Warner Bros.-themed park have held their own against Disney or Universal Studios?

Perhaps, but we’ll never know. After brief periods of ownership, the parks in question were flipped to new owners, in service of the ride-park-roll-up strategy that became the hallmark of both chains, and that the upcoming merger seems to be further continuing.

In this discussion of what Cedar Fair and Six Flags are, we’ve drifted to a discussion of what they’re not. Returning to what they are: both chains are America’s premier ride park chains. They hold parks that maintain the legacy of America’s amusement park glory days, with some parks over 150 years old. They are solid cash-flowing businesses, and for what it’s worth in their own way, they’ve managed to draw an economic moat around themselves – it’s impossible to replace them at their current values.