Table of Contents

ToggleDue to their size, theme parks and attractions are typically financed through creative and diversified sources.

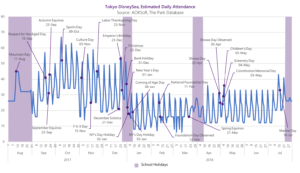

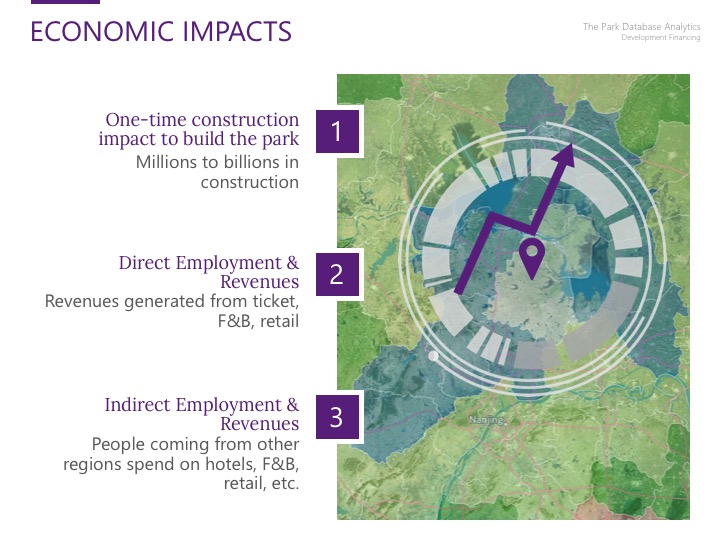

When done right, attractions generate enormous economic impacts. Daily, they can become engines driving a population of people the size of a city within their gates.

This results in trickle down impacts to neighboring businesses, like restaurants, parking lots, hotels, and other merchants. Job growth is created during both the construction of the park, and also on a sustained basis. Tax receipts in the form of property taxes and sales/VAT are also grown and sustained. And for some areas, attractions become a valuable source of foreign exchange or dollars.

All this is to say that for most attractions of a certain size, the local or regional government is an invaluable partner. With manifold economics benefits to the areas surrounding them, theme parks and waterparks are a prime candidate for the public-private partnership model of financing, and any developer or planner must keep this in mind.

Indeed, many of the largest parks in the world have been sponsored either directly or indirectly by the governments surrounding them.

Disney in Paris, Hong Kong, and Shanghai feature heavy government involvement. The Osaka Government was an investor in Universal Studios Japan. Tivoli Gardens was established in 1842 by royal charter, on the grounds that it would distract the populace from mounting social and economic problems. Yas Island’s attractions, including Ferrari World Abu Dhabi, were developed by government-owned Miral.

Indeed, most of the mega-projects in the UAE have been developed under the guidance of government-owned and sovereign entities. Even in the United States, a large proportion of waterparks are municipal-owned and/or operated.

Government Contributions

A summary of the subsidies and contributions that governments typically provide, or can provide:

- Outright cash grants or equity (cash) contributions.

- Land acquisition, appropriation through eminent domain, relocation of residents, or even reclamation.

- Infrastructure construction in the form of metro lines, roads, and utilities.

- Tax subsidies on VAT or accelerated depreciation.

- Lifting of restrictions on zoning or other ordinances.

- Government loans at favorable rates.

- Granting of licensing for residential construction, or other uses like casino gambling.

Other Sources of Funding

Nor is attraction financing limited to government funds or subsidies.

- Initial public offerings (IPOs) are a not uncommon source of permanent capital. As two of the most prominent examples, Euro Disney and Dubai Parks & Resorts were both funded in this manner. Of course, this involves giving up equity and control in return for diversifying the funding sources. But of course, there are sources of funding that do not dilute ownership.

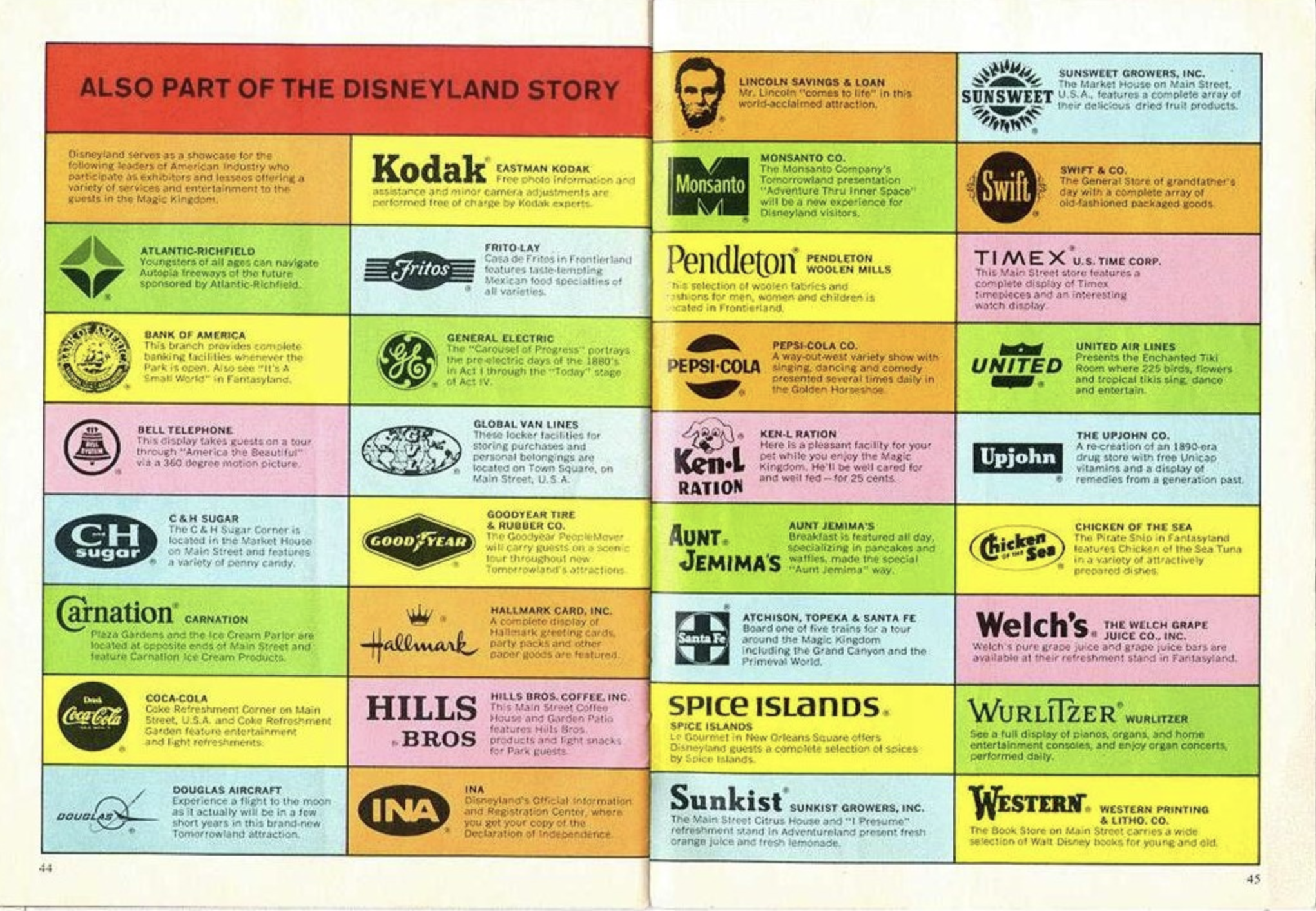

- Sponsorships are probably the best known and frequently used among this category. The original Disneyland was financed in large part by the television studio ABC-Paramount. Afterwards, 33 “lessees” provided ongoing sponsorship to different pavilions and areas of the park. But sponsorships are not limited to parks of this scale. Kidzania, a chain of indoor experiential centers, famously pre-funds its construction through sponsor deposits, and also receives sponsorship funds to the tune of 15-30% of total revenues in this manner.

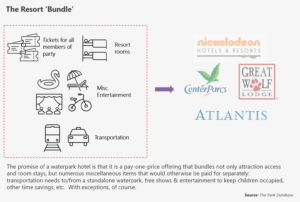

- Peripheral land uses can also be a source of diversified funding. Theme parks in China regularly sell off strata-title retail shops within the grounds of their attraction. And master planned attractions and resorts have the option to sell development rights for hotels, retail, parking, or other land uses in the areas adjacent to the main gate.

Illustrative Example

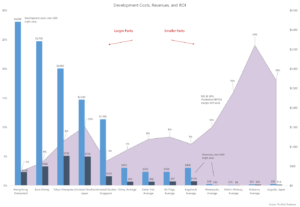

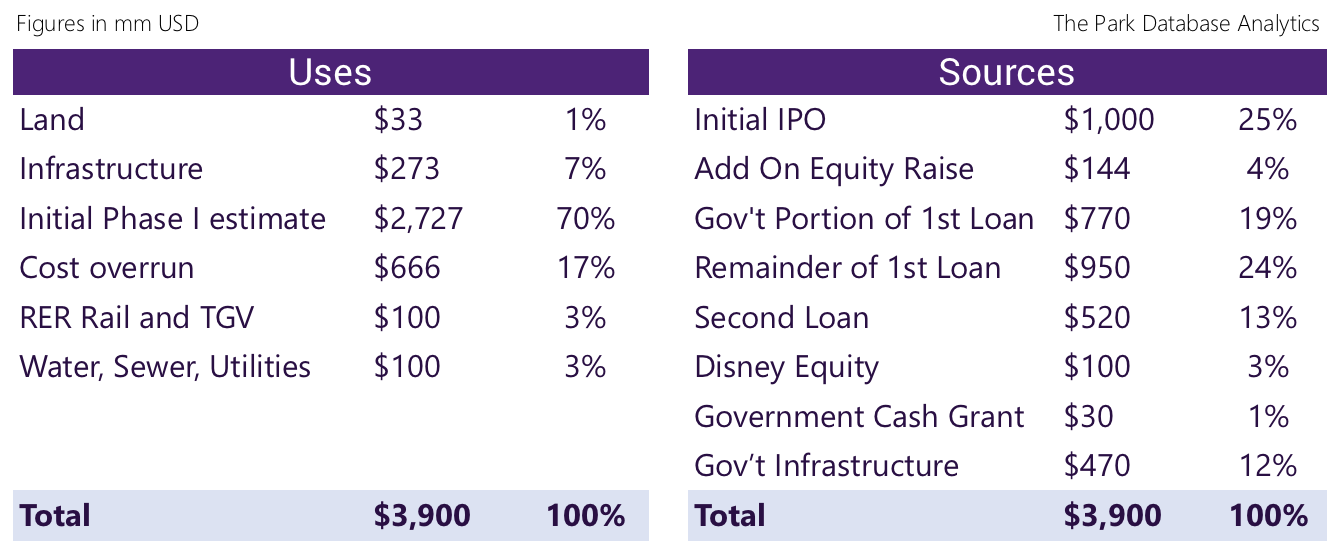

Here’s an example of theme park funding, using Euro Disney S.C.A., commonly known as Disneyland Paris.

- Disney contributed $100 million, which went towards a 49% ownership of the project. The remaining 51% of the project was offered to the public via an initial public offering that raised $1 billion.

- The first loan was a staggering $1.7 billion. The French Government lent $770 million of this amount, the remainder was covered by a consortium of seven banks.

- The government further granted a cash gift of $30 million and contributed over $400 million worth of infrastructure, including an extension of the RER rail and TGV line, utilities, and a subsidy for the land.

- Other incentives granted to Disney included a drop in the tax rate on ticket sales, and an accelerated depreciation schedule (10 years, instead of the standard 20).

- Midway through construction, cost overruns forced a second loan – this time with a consortium with over 60 banks – of over $500 million, and an add-on equity offering, which raised over $100 million.

The economic fortunes were supposed to be further boosted by residential real estate sales in the neighboring area, and the eventual opening of a second gate.

Since opening, the park has gone through multiple rounds of restructuring due to financial problems and unforeseen woes, but the initial financing remains a representative example of the types of funding sources available in the public-private partnership model.

Building on the case of Euro Disney, subsequent government partners to Disney have required higher equity contributions from Disney itself, and have taken actual equity stakes.

****************************

We cover these cases, and others, in our dossier on the financing of major theme parks, now available in our store. For pro users and researchers, may we recommend checking it out.