Table of Contents

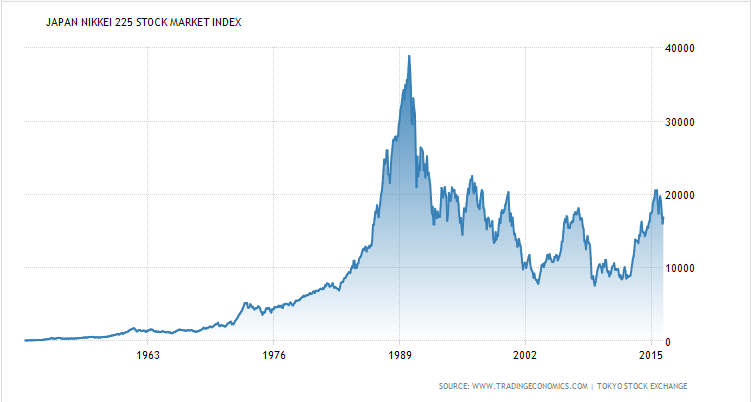

ToggleJapan in the 1980s was a legendary time. The country experienced a stock market and property boom the likes of which has never been duplicated.

The Nikkei stock index hit a peak of over 37,000 in 1989 and a trailing P/E ratio of 60x. It was an explosive boom, followed by a long bust: 30 years later, the Nikkei is still trading at levels nearly a third lower than that peak.

During this time, land was also traded at astronomical levels.

At its peak, land in Ginza was valued at $200,000 a square foot (!!!), or more than $2 million a square meter. Compare this to the record-setting price of “only” $95,000 a square foot set by Henderson Land in its 2017 purchase of 2 Murray Road in Hong Kong, which stands as one of the most expensive land purchases in the world (at least in the past decade).

Valuations were so high that in theory, all the land in the United States could have been purchased for the equivalent of the land under the city of Tokyo.

Foreign embassies in Tokyo began selling parts of their parcels to discharge foreign debt or raise cash. While unfortunate Uganda had to vacate its leased premises because it couldn’t afford the rent, Burma sold part of its embassy for $230 million, which was 3 times the level of its foreign reserves at the time. Meanwhile, Australia sold a garden for $400 million.

For the average person, land prices were increasing so astronomically that 100-year mortgages were introduced, a way of spreading out the cost of a home over multiple generations.

The property boom fed the stock market boom, and vice versa.

Publicly-listed corporations were trading on the value of their land banks, and banks loaned against the ballooning values of these ‘hidden assets’, rather than against cash flow, helping Japanese corporations subsidize purchases and developments both domestically and overseas.

High profile acquisitions in the United States included the $831 million purchase of Pebble Beach golf course, a $1.4 billion purchase of the Rockefeller Center by Mitsubishi, and the $3.4 billion purchase of Columbia Pictures by Sony.

It was an era of excess, in both personal consumption and real estate development.

Within Tokyo, there was talk of building subterranean arcologies and underground cities, with Taisei Corporation announcing a network of offices, malls, and residences comprised of ‘cylinders’ 80 meters in diameter and 60 meters high, burrowed 110 meters underground for a cost of $1 billion – each. Simultaneously, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry announced a $100 million ‘Geofrontier Project’ that would build a dome 80 meters underground and make it habitable.

This would have been cheaper than continuing to erect skyscrapers in Tokyo.

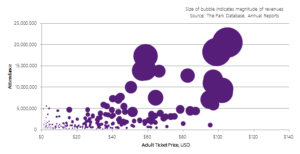

Over a period of three years, between 1989 and 1991, more than 160 golf courses were built in Japan, with another 1,200 under construction or approval. In Hawaii, Japanese developers bought or financed all but two of Hawaii’s main resorts in a six-year period between 1985 and 1991. One of these, the Grand Hyatt Wailea on Maui, was billed as the “most luxurious hotel ever built” and cost $600 million to build, or $760,000 per room. Economists calculated that in order to merely break even, the hotel needed to charge the equivalent of $1,400 per room in today’s dollars and operate at a 75% occupancy, figures that were “impossible in any tourist hotel on earth”.

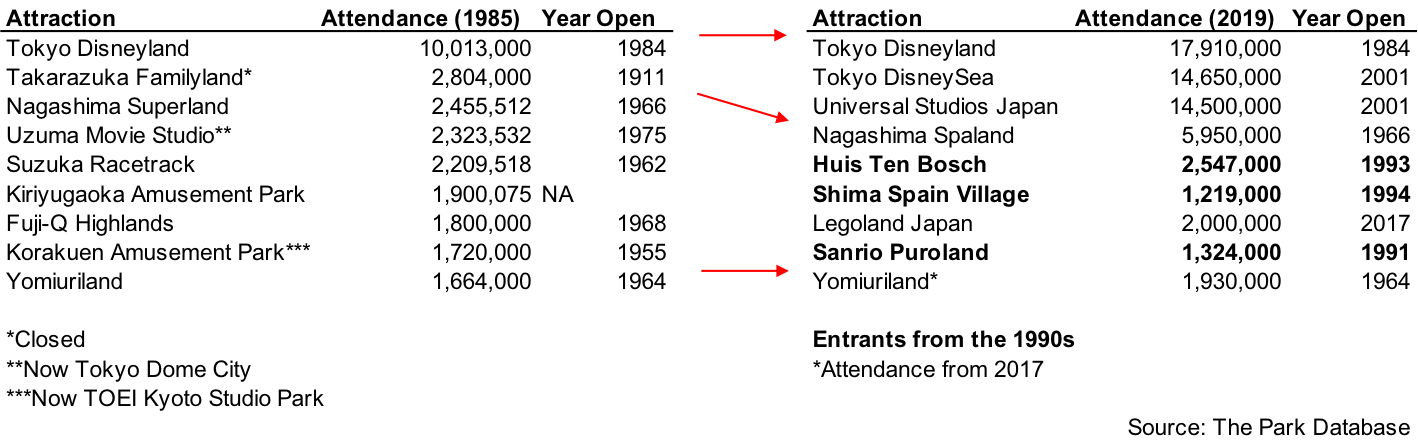

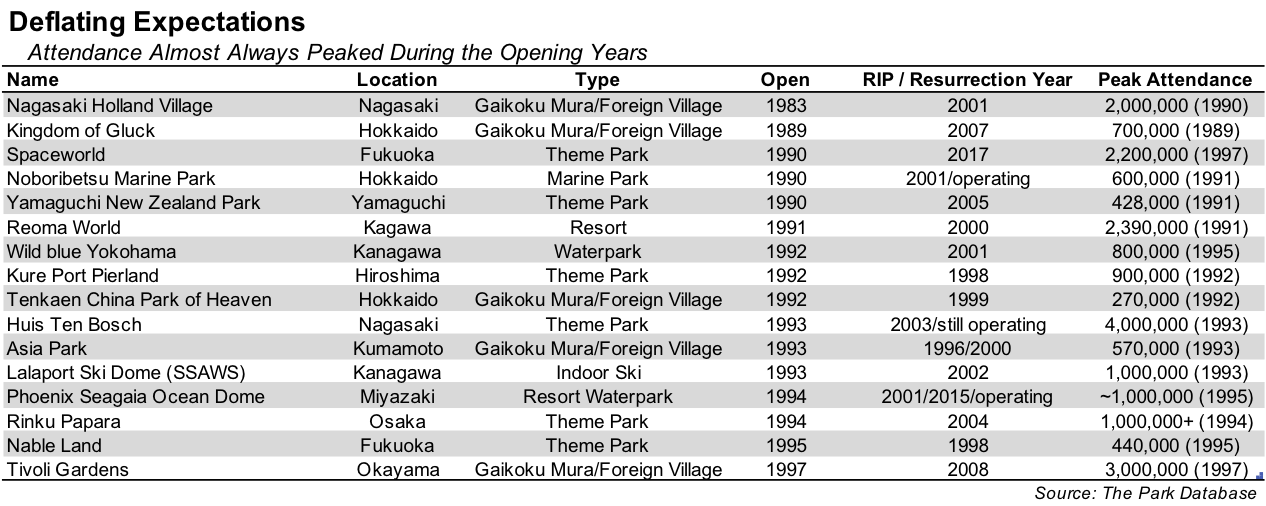

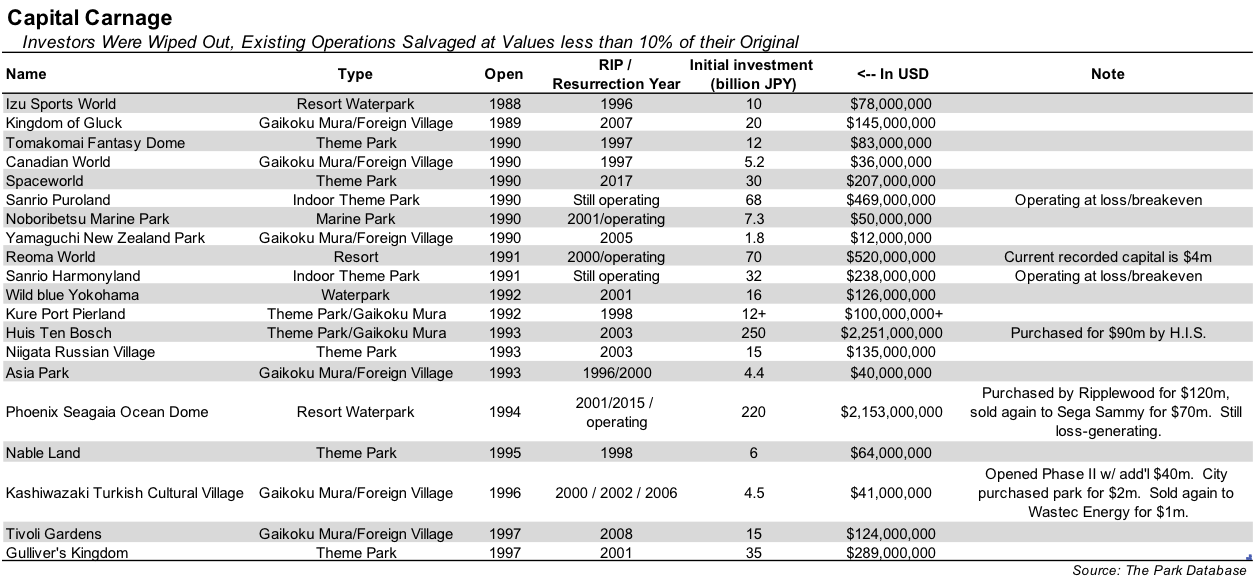

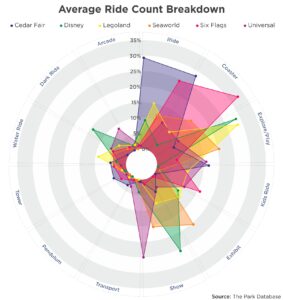

This frenzy extended to the world of theme parks and attractions, with a boom set off by the opening of Tokyo Disneyland in 1983, and a swirling milieu of overly optimistic projections and easy credit.

In 1987, a Comprehensive Recreation Area Development Law (総合保養地域整備法), or the ‘revised Resort Law’ in short, catalyzed development of resort facilities by offering developers tax breaks and loans from the government, in return for local governments developing in alignment with national plans.

For the next decade, scores of theme parks (‘tema paku’ or ‘yuenchi’), attraction-anchored resorts, and what were known as ‘gaikoku mura’ in Japanese, or foreign villages, were developed at a cost of billions of dollars.

Beginning in 1991, land and property values began to decline by precipitous amounts, plummeting at rates of more than 20% a year. However, theme park development continued apace, actually increasing in the 1990s, with much of the white elephants built during this decade. This surge in the face of an implosion in asset prices was often a last-ditch effort on the part of banks, investors, and developers to turn around their fortunes, the equivalent of putting it all on black.

It seems to be the case that local authorities simply did not understand the economics of theme parks, or were hoping against hope that this new thing, the creation of an unprecedented park that didn’t exist anywhere else in the world, would suddenly flood their boundaries with visitors and money.

By and large, it didn’t happen.

Aside from Tokyo Disneyland, opened in 1983, and Universal Studios Japan, which opened safely after the crashing of this tidal wave in 2001, few of these projects remain.

Those that do remain exist only in the memories of wistful blogs or physically abandoned states, as dilapidated, rusting skeletons of their former selves. Others, bought and liquidated several times across several owners, were either razed or passed off to unsuspecting owners.

Some have even managed to stick around. However, most of this latter class are true zombie operations, unable to eke out break-even margins even after 30 years.

So join us in this bit of nostalgia and a trip down collective memory lane. We recommend listening to the classic Japanese City Pop genre (of 1980s vintage) as a soundtrack while you scroll on down.

This post is sectioned as follows. Click on any name to jump:

- Nagasaki Holland Village

- Izu Sports World

- Kingdom of Gluck

- Tomakomai Fantasy Dome

- Canadian World

- Tokyo Sesame Place

- Spaceworld

- Noboribetsu Marine Park

- Yamaguchi New Zealand Park

- Rokko Land AOIA

- Reoma World

- Wild Blue Yokohama

- Kure Port Pierland

- Tenkaen China Park of Heaven

- Huis Ten Bosch

- Niigata Russian Village

- Asia Park

- Lalaport Ski Dome (SSAWS)

- Phoenix Seagaia Ocean Dome

- Joypolis

- Rinku Papara

- Nable Land

- Kamakura Cinema Ward

- Kashiwazaki Turkish Cultural Village

- Tivoli Gardens

- Gulliver’s Kingdom

- The Indoor Odaiba Park Boom

- End of an Era

- Sanrio Zombies

Case Studies

Nagasaki Holland Village

Built over phases beginning in 1983, this was the first ‘gaikoku mura’, or foreign village-style of theme park to be built in Japan. It would be followed over the next two decades by Russian, German, Turkish, German, Danish, and Chinese-themed villages, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

The park was developed by a consortium of local government and banks overlooking Omura Bay in Nagasaki, and achieved a peak of 2 million visitors in 1990.

This success, combined with the financial boom of the period, prompted developers to think much larger.

10 years later, a larger version of the same concept (Dutch village) opened in the form of Huis Ten Bosch, on the other side of the bay.

Unfortunately, the decision to open the much larger Huis Ten Bosch at a cost of over $2 billion meant that neither park could be operated profitably. Nagasaki Holland Village closed in 2001, but was revived by local authorities in 2016 as a retail entertainment center.

Additional Reading:

Izu Sports World

The first of a wave of large scale resorts built during this time period, the Izu Sports World was a 480,000 sqm waterpark-anchored resort opened in 1988.

Construction costs were over $80 million.

With slides, a wave pool, what appears to be a lazy river, a dive pool, tennis courts, spa, and accommodations, the resort heralded the beginning of the build-it-and-they-will-come mentality in Japan, with a location in the resort destination of the Izu Peninsula.

Unfortunately, the resort’s scale was larger than supportable for the market, especially after the financial bubble burst in 1990.

Three years later, the resort was abandoned, and lay in a state of ruin for the next decade until the grounds were razed.

Gluck Kingdom

Signaling the era’s obsession with the wholesale importation of European villages and environments, the Glueck or Gluck Kingdom was a $200 million German village-themed park built in Hokkaido and opened in 1989 at the height of the property boom.

No expense was spared in its construction, as attested by pictures of the hauntingly beautiful structures.

Aiming to faithfully recreate the half-timber houses, castles, towns, and palaces of various popular German destinations, the park’s developer (Zenrin Leisure Land) imported real cobblestone from Dresden, flew over German craftsmen, and spent millions of dollars in importing real German half-timber houses reportedly from the early 1700s.

All this contributed to over 700,000 visitors during its opening year, an attendance level that was sustained for the first few years, until plummeting by more than 50% to approximately 300,000 by 1997.

Financials never broke even during those first few years, however, and cumulative losses seven years after opening had reached $25 million, on revenues of about $6 million.

Zenrin had been overly ambitious. During the initial planning stages for the park, they forecasted hordes of daytrippers flying in from Tokyo into Obihiro Airport to visit the park, whose location was not exactly accessible even for nearby residents.

Three hours from the city of Sapporo, the nearest train station to the park was 23 kilometers away in central Obihiro.

Tomakomai Fantasy Dome

Fantasy Dome was a $120 million indoor theme park built in Hokkaido at the height of the bubble, and it ushered in the era of indoor attraction domes. Advertising what at the time was the novel feature of ‘all weather’ operability, the 39,000 square meter building’s construction cost included only $30 million on the attractions themselves – with the rest on construction of the building and assorted theming.

Hoping for 800,000 visitors a year, the park never achieved its targets and was closed 5 years later.

Canadian World

Despite its name, the park should perhaps have been named after the character it was actually based on – Anne, of Green Gables.

The $70 million park opened in 1992 was yet another one of the ‘gaikoku mura’ foreign village-style theme parks built in Japan during this era, but perhaps most representative of the style of government intervention that characterized many of the theme parks during this time.

Hoping to promote the area as a center for tourism and revitalize the city’s fortunes (as the coal industry was dying), the park was developed by a consortium including the Industrial Infrastructure Development Fund, the host city (Ashibetsu), the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, and Tokyu Agency.

While the mayor of Ashibetsu was appointed as president of the park, management was up to Tokyu – whose role in the park was outsize.

Originally, the 230 hectare area was designated a tourism and leisure facility (theme park) based on stars and celestial bodies, then changed to that of a waterpark theme.

A Tokyu Agency employee named Mrs. Kimura intervened. As an Anne of Green Gables fan, she suggested that as the latitudes of Prince Edward Island in Canada and Hokkaido were similar, that the park should be so designed.

Subsequently the park was named Canadian World and scaled down to 156 hectares, but the first phase of the project had Anne of Green Gables as its theme, complete with lavender field and herb gardens.

In connection with the development were plans for additional ski resorts, golf courses, an astronomical museum, and other leisure facilities. Unfortunately these were not to be. The project closed in 1997, a mere 5 years after opening.

Tokyo Sesame Place

The Japanese version of the Langhorne, Pennsylvania theme park opened in 1990, at the height of the bubble, and stayed open a respectable 16 years – remarkable for its longevity, by standards of that time and place.

Located close to Tokyo Summerland (still operating), the park was designed for young children, with play structures, rope courses, and slides. It closed in 2016.

Built on a hilly plateau, the most remarkable feature seemed to have been the entrance, with the park accessible via a 140 foot long escalator that was at the time, the longest in Tokyo. The escalator deposited you in front of Big Bird’s head.

Additional Reading:

https://muppet.fandom.com/wiki/Tokyo_Sesame_Place

http://bigbirdbridge.blogspot.com/2019/05/the-tokyo-sesame-place-escalators.html

http://bigbirdbridge.blogspot.com/2019/05/tokyo-sesame-place-today.html

Space World

Opened in 1990 by Japan Park & Resort Co, and backed by Nippon Steel, the park opened almost at the precise peak of the bubble on unused Nippon Steel land. It was an attempt, common among many of the developers during this era, to diversify revenues. The feasibility study was conducted by Economics Research Associates (ERA).

One wonders what might have been, as there are no other space exploration-themed parks in the world, and with the right developer and designs, the park could have fulfilled its potential.

But it was not to be.

Its attendance peaked in 1997 at 2.2 million, and declined steadily for the next 20 years. The park attempted various stunts in order to stay open, culminating the opening of an ice rink – with 5,000 fish embedded inside.

The stunt caused public outrage, and both the rink and park closed a year later, in 2017. The ice rink escapade was probably not the cause of the closure, however, as cumulative losses even by 2004, 14 years after opening, were more than $300 million, and attendance hovered between 1 and 2 million for the entirety of its lifetime.

Space World steadfastly denied that its closure was caused by a lack of business.

Space World lives on, however, beyond just the name of the JR Station serving the park.

Before closing, the theme park bought the naming rights to a star in the constellation Taurus, approximately 417 light-years from Earth. This star is named, appropriately, Space World.

Additional Reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Space_World

https://ricebag.net/travelreport/spaceworld-defunct/

Noboribetsu Marine Park

This…was an aquarium inexplicably set inside a Scandinavian-themed castle.

Opened in 1990 for a cost of $50 million in Hokkaido – Noboribetsu, to be exact, the same city as the ill-fated Tenkaen (below), the park still survives today.

This was at a cost of wiping out the investors and debt holders, of which the city of Noboribetsu was one.

Seeing peak annual attendance levels at over 600,000 in the first two years of the park, the attraction unfortunately fell victim to the prevailing economic forces of the time.

Attendance levels plummeted, and in 2001 a major restructuring took place in which the last recorded capital level was approximately $4 million.

During the restructuring process, Noboribetsu City transferred its share ownership of the park entity (Hokkaido Marine Park Co., Ltd.) to its current majority shareholder (Kamori Kanko), along with the assumption of nearly $20 million in debt. The city added on to these subsidies by granting property tax abatements and depreciation breaks on the main building.

However, these measures were enough to keep the attraction afloat – it still operates today.

Yamaguchi New Zealand Village

This New Zealand Village, an agricultural/farm attraction opened in 1990 at a cost of $12 million, is not to be confused with the three other New Zealand villages built during the 1990s and which are all closed today: Hiroshima, Shikoku, and Tohoku.

Accounts are spotty, but it appears that all four villages may have been related, and opened by the magnificently named Farm Co., Ltd., which ran a series of agricultural and sheep-rearing operations, for which these farms were an outlet. These farms were not the only operations that Farm Co. ran – there were other European-themed farms, running into the dozens in terms of count.

Operated as a tourist farm, the Kiwi villages contained onsite factories for agricultural goods such as butter, milk, or baked sweets, offered restaurants, petting zoos, kiddy rides and go karts, as well as a commercial zone full of shops and restaurants.

Attendance peaked at 428,000 during the second year, and plummeted to less than 150,000 over the ensuing decade.

The park was closed in 2005.

Rokko Land AOIA

Many of the theme parks on this list have absolutely heartbreaking stories, and perhaps none more so than this one.

A record-breaking waterpark that opened in 1991 at the tail end of the property boom, pictures of the project show a waterpark that is unlike any other waterpark we’ve ever seen or known. No less than 50 waterslides originated from the mountain at the center of the park.

At the time, 50 slides made it the largest in the world, a record that has still not been broken 30 years later.

Its swimming pool was 740 meters, which made it the longest in Japan at the time, and pictures of the adjacent hotel would not have been out of place in Dubai or Las Vegas.

Unfortunately, the park was levelled in the Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake in 1995 (Kobe), and reconstruction of the park proved to be a prohibitive endeavor. Instead, it was permanently closed, with parts of it sold off for other uses over time.

Reoma World

Reoma was a resort planned at the precise height of the property bubble, with the misfortune of opening in 1991 right when the economic malaise was starting.

It was the first of its breed, a theme park-anchored resort that would be emulated later by the Phoenix Seagaia. At the time of opening, the grounds included a theme park, hotel, golf course, retail entertainment center, and animal park.

The total project budget was 75 billion yen, or an excess of $500 million.

With such a combination of attractions, the resort raced off to a great start, recording nearly 2.4 million visitors in its first year. Unfortunately, this feat would never be repeated. Just three years after opening, in 1995, visitation halved to 1.4 million, then dropped further to 1 million the year before its close.

The resort closed in 2000, to reopen in 2004 under a management system that saw the commercial area, theme park, hotel, and animal park all operated separately as different profit centers. This arrangement lasted until 2010, when operations were consolidated into one entity that consisted of the appropriately named Pain Capital as 65% shareholder.

The new operations started under the name New Reoma World, to be distinguished from the Old Reoma World. It is unknown what the transfer value of the assets were under the various reorganizations, but the operations are currently capitalized at a mere $4 million, less than 1% of the original construction cost.

Wild Blue Yokohama

The Wild Blue Yokohama was an enormous indoor wave pool and beach constructed for $160 million.

It was built in 1992 on land owned by NKK Corp, a major steelmaker with a shipbuilding division, who had hoped its experience with wavemaking machines would translate into waterpark success.

The project never reached the hoped-for level of one million visitors.

Instead, 800,000 was the peak in 1995; it is possible that one of the reasons why can be found in an article published during the time: “Wild Blue Yokohama has found that most people want to go to the indoor beach only in the summer, the same time as they could go to the outdoor beach”

The waterpark was closed in 2001.

Additional Reading:

https://www.thefreelibrary.com/NKK+to+close+Wild+Blue+Yokohama+indoor+pool+complex%2B.-a073853210

http://factsanddetails.com/japan/cat21/sub143/item786.html

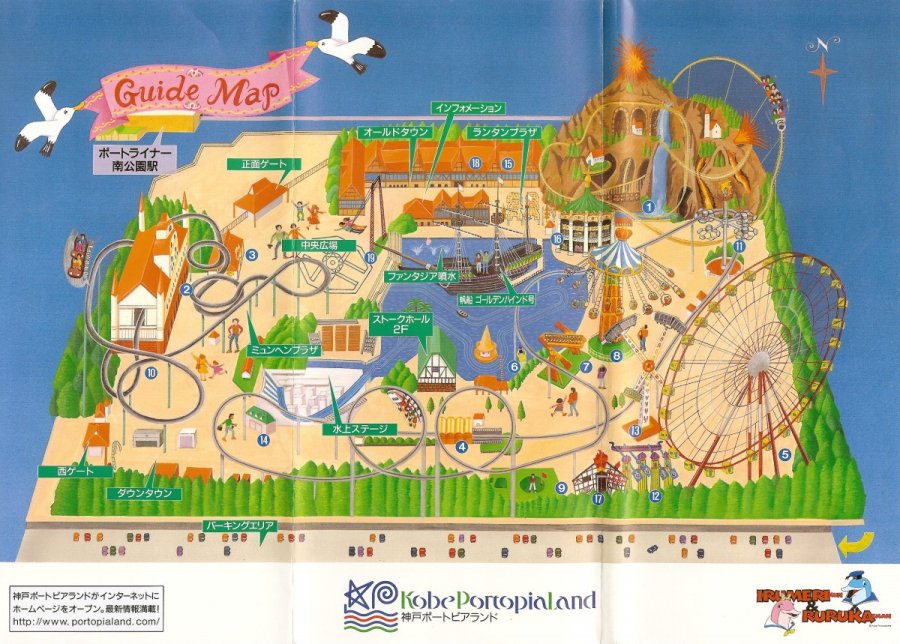

Kure Port Pierland

This Spanish, Costa del Sol-themed attraction was an outdoor theme park located halfway between Hiroshima and Kure City, which funded the development along with Hankyu Corporation.

Hankyu already operated the Kobe Portopia theme park, which had opened in 1981, and it aimed to duplicate the park’s success with attractions that included one of the world’s largest ferris wheels.

In 1992, the park opened to a respectable visitor count of 900,000, but attendance began plummeting soon thereafter. Within a few years, visitation had dropped to 300,000, and the park was closed in 1998.

Debts owed were approximately $100 million. The city took over the park and reopened it as the Kure Portopia Park. Admission is free, and while all attractions have been removed, the absurdly high level of theming provides a nice atmosphere for Kure citizens.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tveLC4mlLig

Tenkaen China Park of Heaven

In 1992, a singularly Chinese-style gaikoku mura opened in Noboribetsu, Hokkaido under the name of Tenkaen.

With Qing Dynasty court gardens and architecture, rockeries, and food and beverage facilities, the park sought to capture the grandeur of an imperial Chinese palace.

It succeeded in attracting 270,000 visitors its first year, but the park’s scale and size (of 40,000 sqm) lacked repeatability. By the third year, attendance had dropped to under 140,000 visitors, a level from which it would never recover.

The park closed in 1999, just seven years after opening.

Huis Ten Bosch

We started this post with Nagasaki Holland Village, and will come full circle with Huis Ten Bosch.

Huis Ten Bosch, meaning House in the Woods in Dutch, deserves special mention in this post. Not only is the original Huis Ten Bosch one of the royal palaces in the Netherlands, the Huis Ten Bosch in Japan was the largest ‘foreign village’ theme park built during this period.

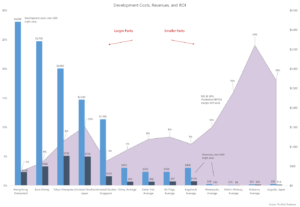

Inaugurated in 1993 at a construction cost of over $2.5 billion, the ‘village’ had truly grand ambitions.

Huis Ten Bosch was not only supposed to be a visitor attraction, but an actual residential village whose overall management, over time, would be returned to the residents. It was already its own recognized administrative unit, its own cho. Over 3,500 homes were planned, along with apartments housing up to 10,000 residents. The first estate was approximately 40% presold by the opening year, of 130 houses and 120 apartments.

To preserve authenticity, no back-of-house facilities were planned in the park – instead, service cars and vans drove right up to their respective buildings to make deliveries. Dedication to authenticity was such that during construction, it was discovered that the left wing of the park’s namesake, the Huis Ten Bosch palace, was 2 centimeters off from the original measurements. It was subsequently torn down and rebuilt, along with a garden that had been planned by Queen Beatrix in the original Huis Ten Bosch, but never built in the Netherlands.

Authenticity pervaded the park in other ways. Dutch city planners were imported to create real dikes with stone, not concrete, in order to prevent the build-up of unsightly mold, and to provide crevices for sea creatures like crawfish and other fish to habitate. Experts in canal-building were likewise engaged, classic taxis from the 1930s were imported to serve as transportation around the park, and a purpose-built natural gas energy plant served the community.

The dedication to a light footprint and self-sufficiency was such that a water plant was also built to filter seawater and provide an exclusive source of fresh water to residents, and all flowers displayed in the park were grown on-site, in greenhouses.

A centerpiece of the park experience was a water show that reenacted Dutch ships sailing to Japan, over which fireworks exploded with musical accompaniment. On this same body of water, a marina was built for sailing yachts, in anticipation for Japan’s burgeoning middle class to become fully rich.

In its opening year, Huis Ten Bosch achieved a visitation level of 4 million. And for the first few years, despite mounting cancellations of the homes, the theme park sustained these attendance levels.

The problem was that even this wasn’t enough to sustain a debt load of over $2 billion.

Ten years later (2003), the park went bankrupt, owing more than 220 billion yen in debt.

The Japanese travel company H.I.S. (previously an acronym for Highest International Standards) purchased the park in 2011. By this time attendance had declined to 1.5 million. Revenues were at a respectable level for any other park, 10 billion JPY ($100 million USD), but the park was losing more than $10 million a year.

The park entered H.I.S. books at a carrying cost of approximately $90 million. You might need to read those numbers again. The park’s initial cost was more than $2.5 billion.

Twenty years after opening, Huis Ten Bosch was losing $10 million a year, and the eventual owners purchased the park for 3.6% of the original construction cost.

However, in its latest full operating year (2019), the park reported attendance of 2.9 million and drastically improved revenue levels of 32 billion JPY ($300m USD). Profits were 7.4 billion, or $70 million.

A spectacular turnaround and success story for H.I.S., although not so much for Huis Ten Bosch’s original founders.

Niigata Russian Village

The Russian Village was the first of three theme parks funded by the Niigata Chuo Bank and its visionary president, Ryutaro Omori. Envisioned as a village of cultural exchange with Russia, the village opened in 1993 as the economic malaise was beginning. Its development cost was $150 million.

Including the now-lost-to-history ‘forest of beer’, folk dance demonstrations, bone specimen exhibitions, a full-scale woolly mammoth, and breeding exhibition of Baikal lizards, the park never achieved repeat visitation nor sustainability.

Its operations were completely dependent on its ability to continue to roll over loans with Niigata Chuo Bank.

When the bank itself went under in 1999, the park was supported by Russian funds until those, too, ran dry in 2003.

The park was closed permanently; unable to find a new buyer, its buildings left to deteriorate. Vandalism and fires took its toll, and the last structure left remaining was the Suzdal Church.

Asia Park

Yet another one of the gaikoku mura themed villages built during this time, the Asia Park was in fact a $50 million ride masquerading as an entire theme park.

It was opened in 1993 by a syndicate consisting of Kumamoto Prefecture and Mitsui Mine, on the grounds of a former…mine.

Conceived of as a park that displayed the splendors of Southeast Asia, complete with a replica of the Taj Mahal and miniature Himalayas, Asia Park charged 600 yen admission for entry into its sole ride, a 15 minute leisurely boat tour of the region’s sights and sounds.

After these 15 minutes, visitors were then deposited back to the main gates, presumably to exit the park.

With such poor planning, it’s a miracle to us the park even survived the 3 years that it did. Unfortunately, pictures of the actual ride are not with us today, and the map is the only artifact that attests to the immersiveness of the experience. Although, judging by pictures of some of the ruins, the replicas may have been miniatures, rather than full-scale models.

After the park’s closure, a go kart track was laid over the original waterways, and the entire experience rebranded as a Sega World complete with arcades.

Unfortunately, go karts speeding blindly through the intricately detailed miniature worlds were not as much of an attraction as hoped, and this project, too, was closed and demolished for good in 2000.

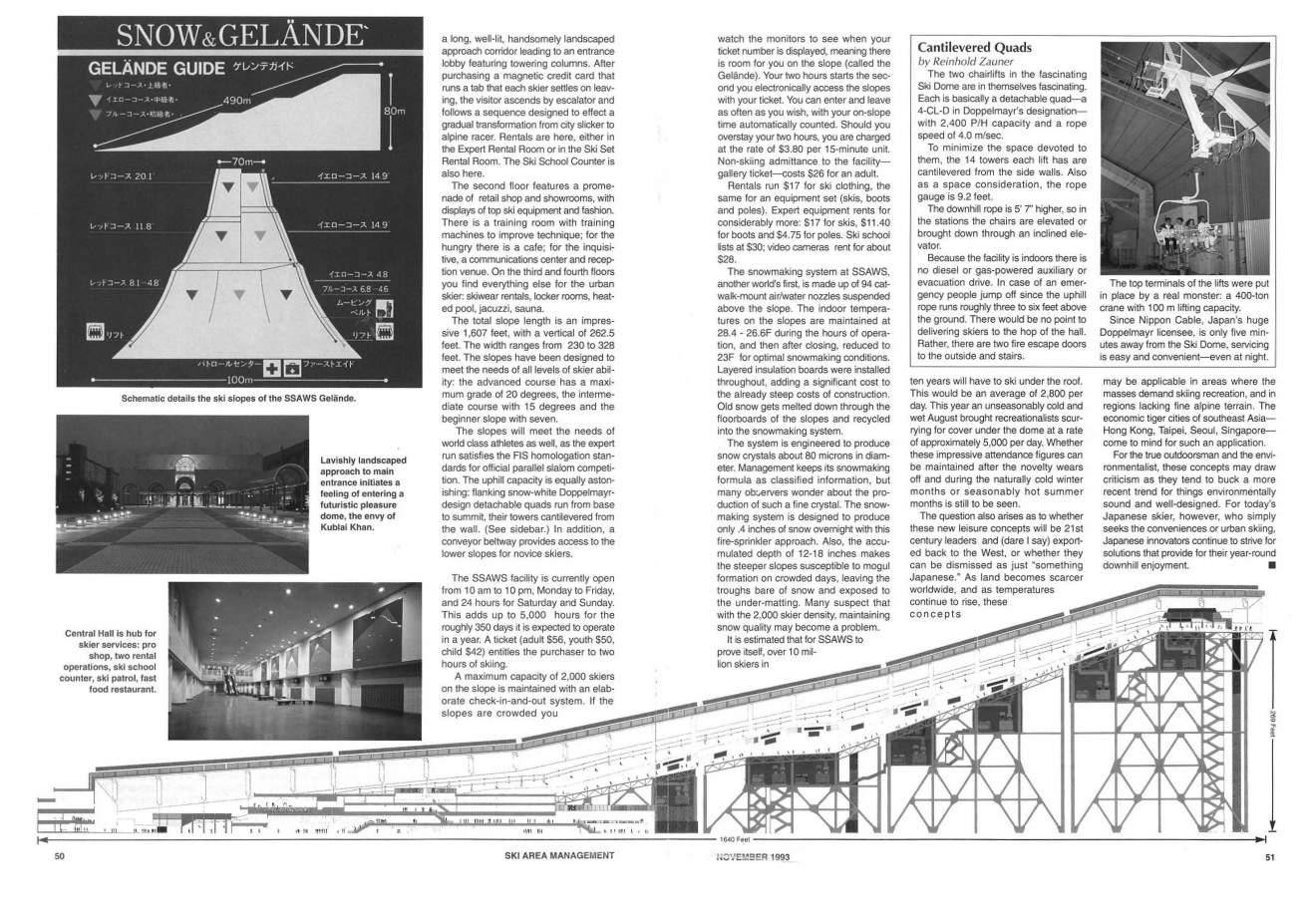

Lalaport Ski Dome Yokohama (SSAWS)

Continuing the sport trend, we introduce here the Lalaport Ski Dome Yokohama, another forgotten megalith in the history of Japanese real estate development.

Built for $400 million back in 1993, it was the largest indoor ski dome in the world at the time, with a slope length of 1,600 meters – a figure that would still put the project in the ranks of the top 4 indoor ski slopes today.

Its massive construction cost was equaled by Ski Dubai (also $400 million) nearly 22 years later, in 2005, but with a slope length that did not measure up to Lalaport’s.

The Ski Dome was built by Mitsui, and used as much energy per day as the Empire State Building. It broke records on several counts, including an unprecedented snowmaking system, but wasn’t able to escape its own excessive expectations.

The project achieved a breakeven visitation level of 1 million guests the first year, but the second saw a 30% drop in attendance. Saddled by interest and taxes of over $30 million a year, and operating costs of $40 million, annual losses were $15 million a year, and forced the project to close just 9 years after opening.

A feasibility study had indicated that it would take the project 11 years to reach profitability at a visitation level of 1.3 million annually, and repay debts after 18 years.

The site is now used by Japan’s first large-format IKEA.

Additional Reading:

Source 1, Source 2, Source 3, Source 4, Source 5

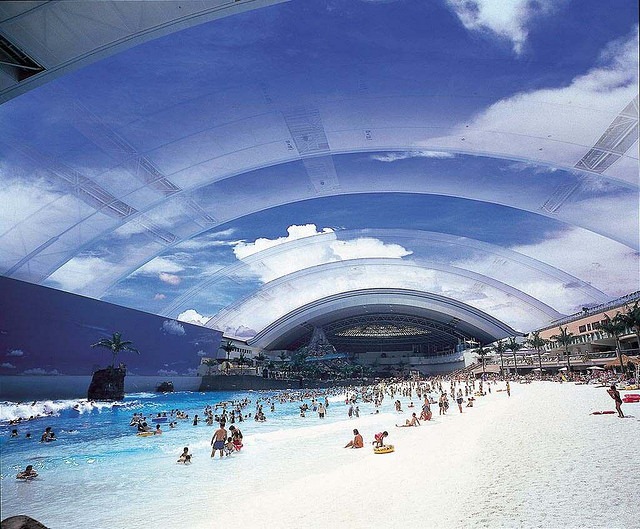

Phoenix Seagaia Ocean Dome

This resort, located 5 minutes from the ocean in Miyazaki, is often used as one of the poster children for the Japanese real estate bubble. Although relative to this entire list, it seems almost…average.

Opened in 1993, the Ocean Dome was the centerpiece waterpark of the Phoenix Seagaia resort, comprised of hotels, a golf course, convention center, among other leisure facilities. It was an indoor waterpark set underneath a 33,000 sqm retractable roof that opened to the elements during temperate days, and closed back up when the weather became more inclement.

The underbelly of the retractable pool, when closed, featured an artificial sky that simulated sunny skies and at night, a starry galaxy. Unfortunately we weren’t able to find photo evidence of the latter, whose appeal is left to the imagination. One can only imagine the sight of a starry sky set above the erupting volcano that served as a backdrop.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3VaTuBIV_SI

A wave pool was the central attraction, fronting a white sand beach that was reportedly the longest artificial beach in the world. The sand was not actually sand, but glistening mounds of crushed marble whose attraction was that it didn’t stick to skin.

Two years after opening, in 1995, the Ocean Dome attracted a little over 1 million visitors. That was the peak.

Unfortunately for the financiers and investors of the project, of which the local authorities were a major group, the $2 billion resort accumulated losses of over $1.5 billion by 2000, a mere 7 years after it was opened, prompting a sale the next year to Ripplewood Holdings, a US private equity firm. The golf course was sold separately 3 years later.

Ripplewood ‘saved’ the resort by buying it for $120 million, or at a 95% discount from its original cost, and proceeded to invest another $70 million into it.

Several years of operations even under a Starwood brand name weren’t able to turn it around, however. Annual reports from 2005 show the resort recording losses of $25 million annually.

10 years later, Ripplewood sold the holdings to Sega Sammy at another 50% haircut relative to capital invested: for $70 million.

In its latest annual report, it appears the Phoenix Resort is continuing its ways, however, with losses during the Fiscal Year ended March 2020 of…$25 million.

Additional Reading:

https://www.segasammy.co.jp/english/pr/business/resort/

https://www.segasammy.co.jp/english/ir/library/printing_annual/

https://bib.kuleuven.be/files/ebib/jaarverslagen/RHJInternational_200405eng.pdf

https://www.amusingplanet.com/2012/01/seagaia-ocean-dome-artificial-beach-in.html

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2004/12/17/business/phoenix-resort-to-sell-golf-course/

https://www.segasammy.co.jp/english/ir/library/pdf/printing_annual/2019/al2019_all_e__.pdf

http://www.orangesmile.com/extreme/en/greatest-aquaparks/seagaia-ocean-dome.htm#object-gallery

https://web-japan.org/atlas/architecture/arc27.html

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2000/jul/12/jonathanwatts

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/ripplewood-to-invest-another-dollar23m-in-seagaia-kqjm5dhwp0x

Joypolis(es)

Locked in a death match with Nintendo on the videogame console front (Game Gear vs. Game Boy, Genesis vs. Super NES), Sega in the 1990s sought to diversify its revenue streams by turning to location-based entertainment.

You might be familiar with the Joypolis Tokyo indoor theme park (still extant), but it’s likely you’ve never heard of Joypolis Yokohama, opened in 1994 before Tokyo or Joypolis Niigata (ah, yes, Niigata) in 1995. You probably also haven’t heard of Joypolis Fukuoka, Shinjuku, Okayama, Kyoto, or Osaka, which were all opened in a three year frenzy between 1995 and 1998. All were closed, folded into arcades, or downsized within a decade of opening.

Not content to stay within Japan, Sega expanded its reach overseas, with a Sydney Sega Works, which was a freestanding satellite to a sprawling franchise of Sega-themed indoor theme parks worldwide.

In the UK alone, no less than 26 different Sega Parks, Sega Worlds, and Sega Megaworlds included the latest high tech Sega videogames, bowling lanes, and merchandise. These were a cousin to the Sega-Dreamworks joint venture Gameworks in the United States, which operated on a similar arcade and F&B concept, as an early predecessor to Dave & Buster’s.

Currently 27 locations are closed to the 7 still operating, having gone through two bankruptcies and changes of ownership.

Additional Reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joypolis

https://segaretro.org/SegaWorld_London

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SegaWorld

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/GameWorks

Rinku Papara

This Osaka-based park met the unfortunate fate of not only being located in the same city as the eventual Universal Studios Japan, but developed in a further-flung location than the megapark.

But when Rinku Papara opened in 1994, the park soared to an auspicious start. Recording more than 1 million visitors within the first two months of opening, the park appeared to have tapped into a pent-up demand.

Unfortunately, visitation was not sustained. We suspect the small size (just over 20,000 sqm) and lack of reinvestment were to blame, but whatever the reason, attendance dropped by more than 30% to the 600,000-700,000 range just a few years later.

With the opening of Universal Studios Japan in 2001, the Osaka government began to turn its attention – and priorities – elsewhere.

In 2004, Osaka requested a rent bump in the land lease that the park could not accommodate, forcing its closure just a decade after opening.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6u9iVOBhiFE

Nable Land

The spectacularly named Nable Land, so-called for its location at the center of Kyushu (“navel”), was opened in 1995 for more than $60 million.

Navel, no, Nable Land was constructed in Omuta City, Fukuoka Prefecture, on the grounds of the former Mitsui Miike Coal Mine: with the loss of the industry, Mitsui Chemicals, Fukuoka Prefecture, and Omuta City signed up for the underlying trend of the era, which was to convert previously industrial land into amusement parks.

It was a sentiment that we can only interpret as being somewhat of a desire to prettify previously dreary surroundings to the extreme.

Nable Land hosted a variety of amusement park rides, including the respectable Zierer-built Super Dragon, an aquarium, as well as a sub-tropical botanical garden and a suspiciously gaikoku mura-style entry façade. In a throwback to its roots, it included a coal mining museum. Alas, there were no belly buttons or oranges.

We feel the whale trapped in the entryway could have been taken a lot further, but the statue is all we get.

Nable Land opened with an auspicious 440,000 visitors, a great base to build attendance from. However, the small size of the park discouraged repeat visitation, and attendance dropped steadily. Three years after opening, the park closed with a $60 million debt load.

Subsequently the park was dismantled and repurposed, with Omuta City transferring 4 hectares of the land free of charge, and deciding to continue operating the coal museum free of charge.

Additional Reading:

https://ricebag.net/travelreport/navelland-defunct/

Kamakura Cinema Ward

Conceived of during the late stages of the boom, the Kamakura Cinema Ward’s concept was of a ‘world that will never be completed’. It was a $150 million project built on the premises of a former film studio.

A three story indoor park that opened in 1995, the park hosted a variety of movie sets and stages, props, and rides in a 28,000 square meter space. Over three floors, the park introduced sets and attractions related to Japanese and American cinema, and on the third, an inexplicable space station with alien robots. A playground meant for kids was hosted on the roof.

Unfortunately, mounting losses culminated in the project closing just three years after opening, posting a $16 million loss that year.

Additional Reading:

https://blog.goo.ne.jp/ska-me-crazy2006/e/29207b5fd6959c113402f1085e4d6475

http://www.kana-chiri.org/chiiki/kawariyuku/Ofuna2.html

Kashiwazaki Turkish Village

The second theme park venture funded by the famous Niigata Chuo Bank (after the Niigata Russian Village), the Turkish Village was funded for a more modest $60 million (first phase) and was a recreation of Istanbul, complete with product sales, statue of Ataturk, a Trojan horse, Noah’s Ark, belly dancers, mosques, and amphitheaters.

Opened in 1996, this village also failed to attract visitors. In response, just two years after opening, the village doubled down.

But borrowing an additional $40 million to build a second phase to the park did not help its fortunes, and the park closed just two years after that.

Kashiwazaki City purchased the park for $2 million (98% discount in case you’re keeping track) and leased the park to tour operators, while lowering the ticket price to the bargain-basement level of free.

Two years later, however, the park was closed yet again over the appeals of the Turkish Embassy, who proposed a rebuilding.

It was liquidated with cumulative losses of another $2 million and sold for little over $1 million in 2006 to Wastec Energy, a local industrial waste recycler, who opened a wedding resort adjacent to the village.

The statue of Ataturk was moved to a politically appropriate location.

Additional Reading:

http://home.k07.itscom.net/jf1dcu/Trip_around_the_globe_Folder/Turky/turkish_village.html

Tivoli Gardens Kurashiki

As we enter the late stage of the boom, there were several more spectacular flameouts waiting in the works.

Licensing the Tivoli Gardens brand from the Danish park of the same name, Tivoli Gardens Kurashiki was financed by the local government of Kurashiki City and opened in 1997.

Construction costs were in excess of $150 million, but the park struck a chord with visitors, with nearly 3 million the first year, easily outpacing most other parks in Japan.

However, like every other park on this list, attendance went in the other direction than hoped for, with less than 800,000 during each of the last two operating years of 2007 and 2008.

The relationship with Tivoli Gardens International was terminated, and the park closed down, with $150 million in debts that would not be repaid.

Additional Reading:

http://factsanddetails.com/japan/cat21/sub143/item782.html

https://usmodernist.org/AL/AL-1997-10-11.pdf

http://www1.econ.hit-u.ac.jp/glp/2014/eu2014.pdf

https://wenku.baidu.com/view/19ccd8cc0508763231121278

Gulliver’s Kingdom

This theme park based on the book by Jonathan Swift was opened in 1997, at the tail end of the theme park boom.

Developed by the Fuji Chuo Group for a cost that exceeded $350 million, the park collapsed a mere 4 years later.

The Niigata Chuo Bank, the main lender to the park, held loans related to Gulliver’s Kingdom on its books for over $350 million, and took a loss on the entire amount. The Kofu District Court, overseeing the region, auctioned off the park and what was left of its assets for a massively shrunk, Lilliputian amount of $20 million in 2002.

Although there might be various reasons why the project closed – exorbitant costs, for one – the surroundings of the park did it no justice. Bordered on one side by Japan’s suicide forest, and on another by the location of the sarin gas attacks, the park was unfortunately surrounded by negative aura.

Additional Reading:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2002/11/22/national/gullivers-kingdom-finally-finds-a-buyer/

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2001/11/13/national/kamikuishikis-gulliver-park-falls/

https://www.michaeljohngrist.com/2009/04/gullivers-kingdom-haikyo-rip/

The Indoor Odaiba Park Boom

Joypolis opening in Tokyo lit another short lived, late-stage boom. Or fizzle.

At the end of the 1990s, as we reach the expiration date for most of the parks on this list, attention turned to novel ways of delivering theme park experiences.

Such as moving indoors.

It might be the case that companies, mistaking Sega’s Mega moves both domestically and overseas in the LBE realm for success, were quick to attach themselves to the trend.

Perhaps the opening of location-based attractions held an appeal for companies whose core competencies were nothing close to it.

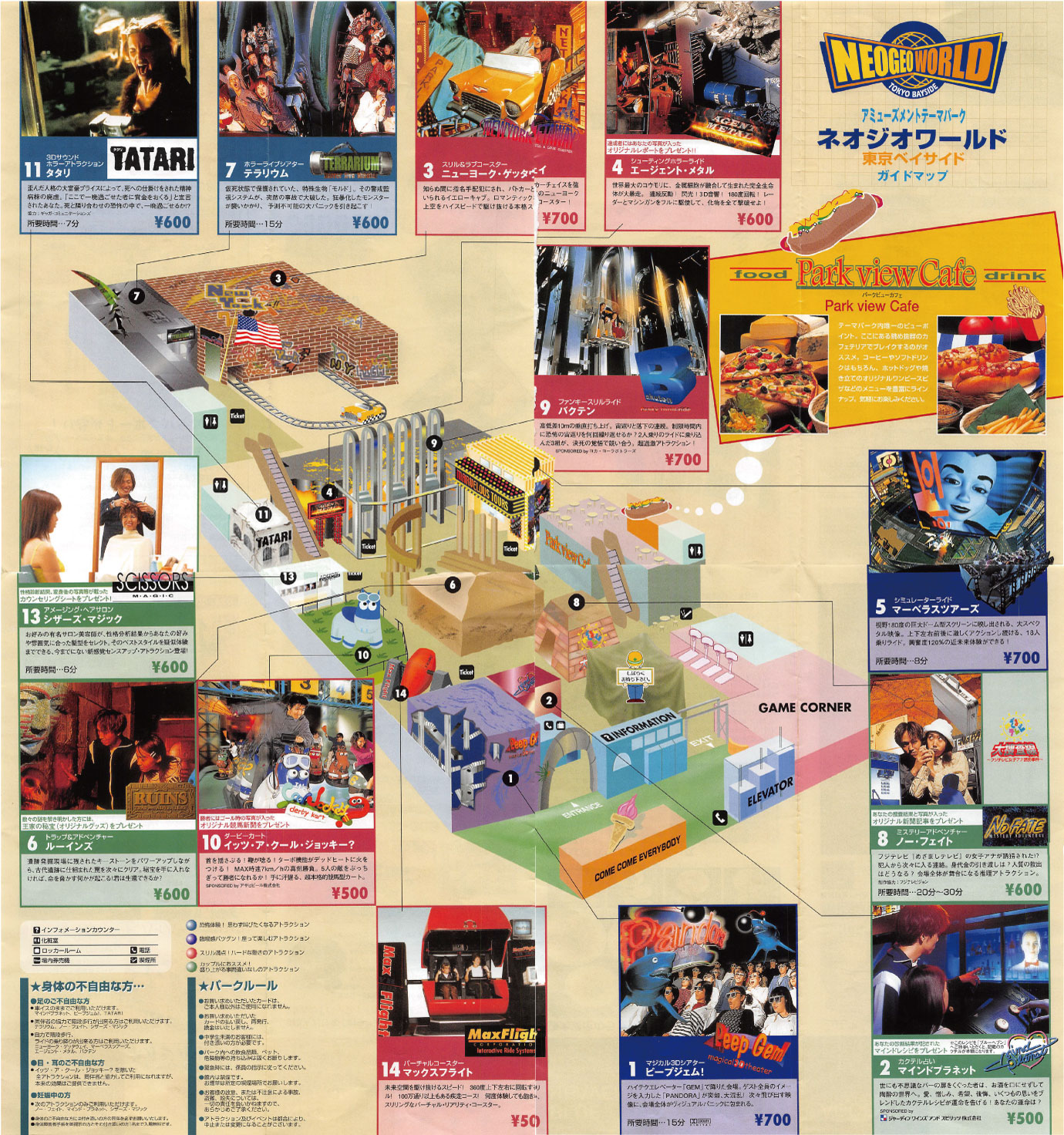

Over the short period of 1996 to 2000, all in Odaiba, the Tokyo Joypolis opened, followed by a Toyota amusement facility in the form of the still-extant Megaweb. The same year, SNK opened Neo Geo World, with a theme based on videogames of its eponymous console, followed shortly thereafter by Sony’s indoor park Mediage.

Neo Geo World

Seeking to expand beyond just the game consoles and arcade games that made its name, SNK opened the first of its two LBE centers in Tsukuba, north of Tokyo, in what would be a test pilot for Neo Geo World in Odaiba

Neo Geo Tsukuba featured off-the-shelf attractions such as IMAX rides and neon bowling alleys.

In Odaiba, SNK sought to capitalize on the success of its videogames in Neo Geo World…by building a park almost devoid of its hit videogame content.

Images of the park during its heyday are almost nonexistent (except for grainy late 90s-era pics like the one below), but the landmark attractions in the park included such gems as a New York-cab themed roller coaster, haunted house, motion theater- and simulator rides, and a fortune-telling themed attraction(?).

The attraction was operated on a pay-as-you-go basis, although passport/POP pricing of 3,400 JPY was available.

Other highlights in the chambers included a 44-lane bowling alley, 19 karaoke rooms, and a cafe with billiard tables.

The park was closed 2 years later, in 2001.

Additional Reading:

https://ricebag.net/travelreport/neogeoworld-defunct/2/

https://ricebag.net/travelreport/neogeoworld-defunct/

Sony Mediage

Mediage was a truly original – and based on the theme parks we’ve seen over the years, we don’t use that word lightly – indoor theme park concept.

The originality, however, stretched the limits of good attraction operating practices.

For example, the attraction had only 5 rides or experiences, and three of them were based on the well-known themes of…Coca-Cola, Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, and the Beatles.

These five were upcharge attractions that charged between 300-800 yen, but it appears at least one of the experiences was a game that allowed unlimited access (measured in time) for just 800 yen.

Which meant that with only 5 attractions total, guests were left waiting for uncomfortably long amounts of time as prior guests entered the capacity-constrained experiences and never left.

The Coca-Cola themed attraction was a modified bumper car that saw visitors try to maneuver their car into certain positions – but in the queueing area, visitors also had the option of drinking as much Coca-Cola products as desired.

We can only assume that the resulting tension between these two ‘experiences’ was part of the experience.

Where the Wild Things Are was a multi-level playroom for young children themed after the book by Maurice Sendak, the Yellow Submarine adventure was a simulator based on the Beatles song of the same name, and the Airtight Garage was a series of 3 experiences consisting of a shooter, a bowling alley, and spaceship-like ride. It was based on the French comic strip of the same name.

Unfortunately the attraction closed after 2 years, in 2002. It reopened the same year as a free showroom displaying Sony products.

Additional Reading:

https://ricebag.net/travelreport/defunct-mediage/

End of an Era

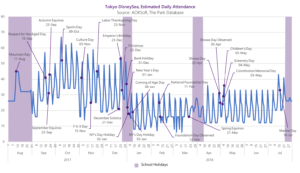

In 2001, both Tokyo DisneySea and Universal Studios Japan opened, marking the end of a 15 year boom in homegrown theme park development.

With the entry of the two majors (Disney & Universal), it was as of developers began to realize what a theme park actually was. Even though Tokyo Disneyland opened in 1983, the park’s success seemed to have been dismissed as a fluke until the two others opened.

Their success also began encroaching on the business of other parks, and Universal Studios in particular appears to have been singularly responsible for a number of fatalities, including the previous Rinku Papara, as well as a pair of parks operated by Hankyu Corporation.

Although both parks were opened far earlier than the beginning of the theme park or real estate boom (earlier than even Tokyo Disneyland), the Takarazuka Familyland and Kobe PortopiaLand parks were both facing declining attendance throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Takarazuka Familyland opened in 1911, and saw steady attendance of over 2.5 million a year during the 1970s, and 2.8 million even in 1983, a few years after the opening of Tokyo Disneyland. By 2001, however, that figure had fallen to 1.1 million, victim of what was possibly a lack of reinvestment to keep up with the times.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WfVa4PRdv1s

Kobe Portopia opened in 1981 and by the mid-1980s, was generating attendance of slightly over 1 million visitors annually. In 1991, at the peak of the bubble era, this park too hit a peak of 1.6 million visitors until dropping to less than 500,000 by the end of the decade.

Zombies

And so it goes with much of the era’s existing parks.

This in summary encapsulates much of the fate of the Japanese theme park industry: a park built extravagantly, and with a mix of incentives and bubble-era optimism that turns it into a zombie. When the zombie economics of the theme parks become too much to bear, it closes. Permanently.

If it doesn’t, the park continues on at levels far below the peak, rarely thriving. See: Phoenix Seagaia.

As another example, the Sanrio company built two parks at the exact height of the property bubble. The 20,000 square meter Puroland was built for a cost of $500 million in the outskirts of Tokyo and opened in 1990. A year later, the much smaller Harmonyland opened for $200 million in Oita.

Both were designed by Landmark Entertainment, who received $50 million for its efforts. Puroland, in particular, consists of a show extravaganza & boat ride intermixed with stores, characters, and upcharge attractions, calling to mind the ill-fated Asia Park.

Both parks have generated operating losses of between $2 and $7 million for at least the past decade, if not longer, with a last recorded operating loss of 200 million JPY (~$2 million) in 2017.

Effectively, these parks are 30-year old zombies.

In theme park industry lore, the Sanrio parks were supposed to be have been built as a gift from the Sanrio chairman to the people, although at nearly $700 million in combined development budget, the parks were quite an extravagant gift indeed.

In Summary & Lessons Learned

The majority of the parks that were built in the 1980s and 1990s were quick to enter the industry, then leave.

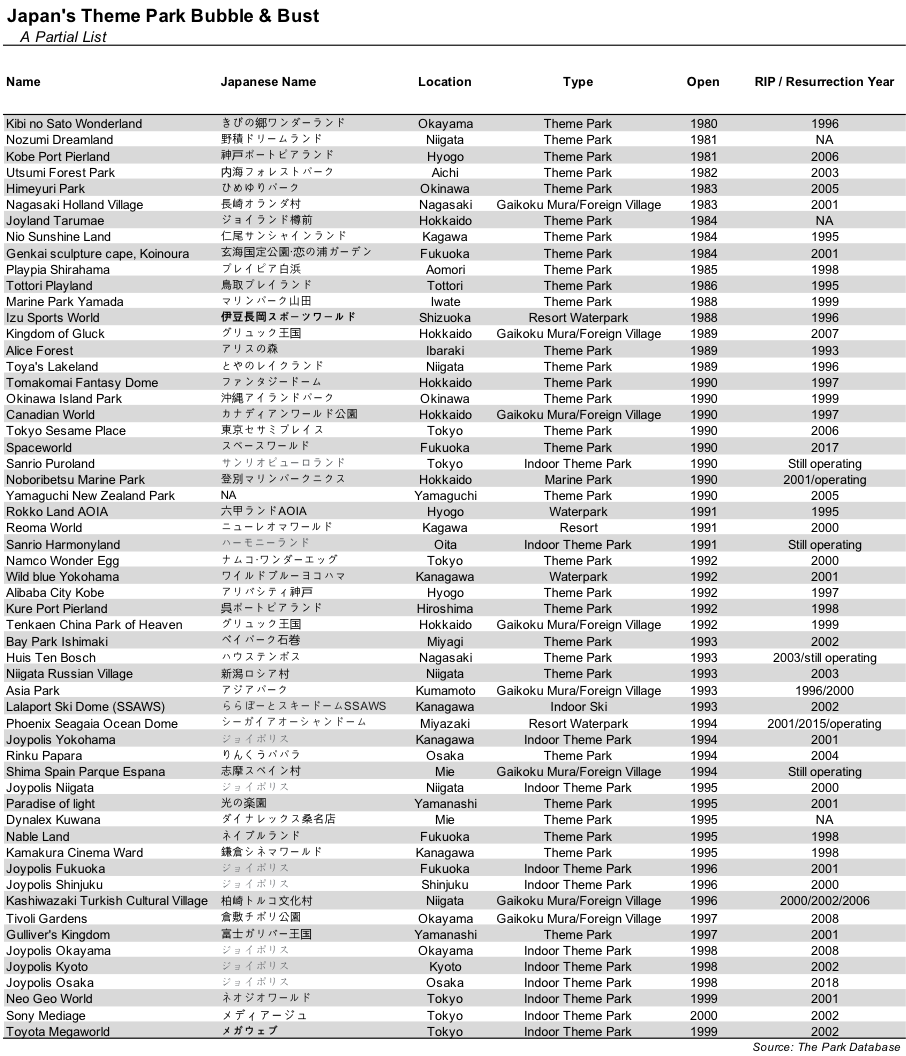

If you had prepared a Top 10 list of theme parks by attendance in 1985, as Harrison Price Associates so helpfully did, and compared it to now, the list would hardly contain any parks from the 1990s, except for a park that was rescued out of bankruptcy, one that’s a zombie, and at least one surviving gaikoku mura.

It’s hardly what you would expect for a country that saw a theme park boom erupt for the subsequent 15 years. Tokyo Disneyland remains at the top spot in the list, joined by its second gate, DisneySea. Universal Studios Japan and Legoland are new entrants, and Nagashima Superland (now Spaland) has moved up a few notches, there are hardly any other entrants.

As we’ve noted before, the persistence of cumulative advantage in this industry is great, and the power of well-capitalized, visionary major brands is undisputed.

What were the causes of this boom? While it’s all too easy to say ‘easy availability of credit’, the fact that more than half the parks on this list were built after the property bubble had popped in 1991, bears some deeper examination.

At least some of the cause is attributable to legislative inducements; specifically, the 1987 Resort Law.

Under this legislation, local governments eagerly offered up unused plots of land to developers, who received tax breaks and favorable loans in return for revitalizing previously abandoned coal mines and dilapidated land.

As an unintended consequence of this law, however, local governments began to enter these transactions as principal parties (as investors) without clearly understanding the economics of the parks.

As development proceeded under this law, the mania grew to unmanageable levels as governments and developers alike began to rely on hope, rather than reality. This became especially pronounced after the financial and larger property bubble popped in 1991.

It almost appears as if banks, governments, and developers alike began to think – or believe – that theme parks and attractions would be the salvation of the nationwide malaise or their companies misfortunes. Banks, such as Niigata Chuo, began to pour hundreds of millions of dollars into projects while relying on the most optimistic scenarios.

Excessive optimism as a cause is almost certainly a factor, but unlike the others, it’s difficult to quantify or support. We can only see evidence of this sentiment in the sheer number of white elephant projects built after the property bubble began deflating in 1991, and in anecdotes such as Gluck Kingdom built with no means of public transportation nearby.

Magical thinking pervaded the nation and infected all sorts of parties, like Mitsui hoping that a 15-minute ride would suffice as a theme park, or its forays into the world’s largest ski slope.

Or videogame companies like Sega and Neo Geo expanding into the highly non-scalable, heterogeneous business of Location-Based Entertainment, believing there was some sort of magic pill that would aid their business expansion.

And the government can’t be excluded as a culprit either; both local and federal agencies like the Ministry of International Trade and Industry were behind plans for underground cities as well as theme parks such as Canadian World.

Theme park success or failure is often a function of longevity.

Universal Studios Japan was barely break even for the first few years after opening. Yet a large portion of Japanese theme parks opened in the 1990s did not care to see losses for more than 2-3 years before shuttering their doors.

One can only wonder what would have happened if the vast majority of these parks had solid business plans, visionary founders, or patient sources of capital behind them.

Yet most did not, and this point harkens back to a previous one, which is that many of these developments were clearly undertaken by parties such as local governments, who were either not committed to, or not in, the theme park business. This led to a fetishization of the theme park land use type, especially in the form of gaikoku mura, or foreign villages, with corresponding lofty hopes for what such a project could do for their municipality.

Theme parks often need a belief to help sustain them, and in the case of most of these parks, their founders had a misplaced one.

On a more general note, what some of these parks seem to indicate is that a bad business plan…is simply a bad business plan.

Even after wholesale value destruction, many of the parks that were salvaged out of bankruptcy at prices that were less than 5% of their original construction cost, still managed to fail.

Goldman Sachs-backed Ripplewood Holdings was unable to salvage the Seagaia Ocean Dome, and it continues generating losses under a third owner. The Asia Park was salvaged out of bankruptcy by Sega, only to closed shortly afterwards. And the Kashiwazaki Turkish Cultural Village shut its doors no less than three different times, in what became a biennial tradition for the city.

No one who builds a theme park or an attraction is a pessimist.

Those who bring these fantasy worlds of the imagination to life are necessarily visionaries and dreamers, and even in the rusting, dilapidated ruins, in the zombie operations, and huge empty land plots where structures have been removed or repurposed, you can catch glimpses of a particular time and era. These ghosts remain with us today as emissaries of a time of unbridled optimism and hope for the future.

Even while documenting the particular madness of this era, we celebrate the risk-takers and visionaries who at least tried spectacularly. Their efforts left behind relics of a time of unbridled optimism, a real estate and stock market bubble whose likes had never been seen before, a place and era that is unique in the history of the world.

For anyone in Japan, we encourage you to go check them out, abandoned or not.

Interested in this topic? Be sure to check out our founder Won’s authoritative book on the subject.